X’s Excesses on Soyinka’s Verbosity: A Nabokovian Defense.

I.

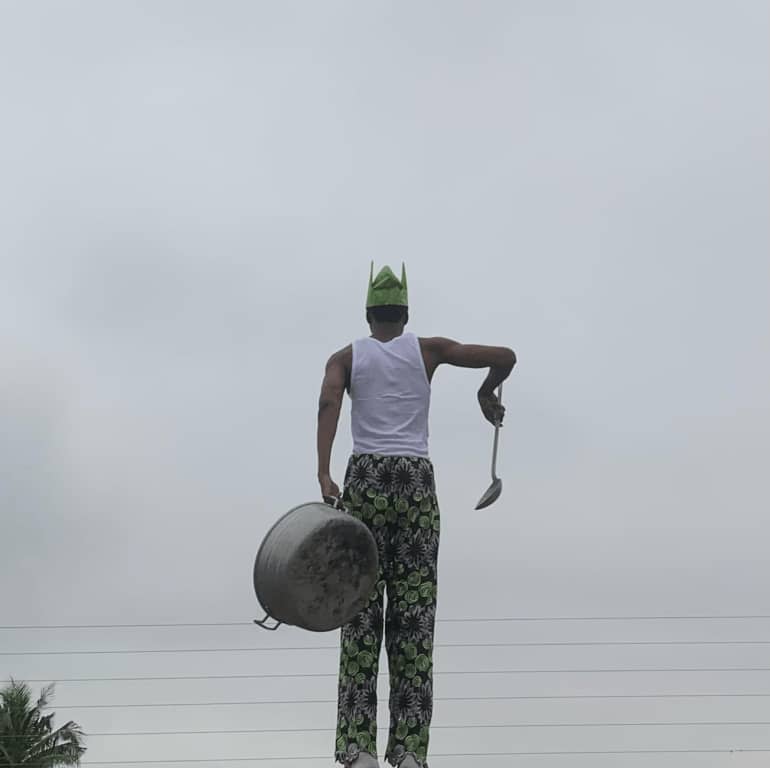

One may begin from the locus of thumping despair. One may end with the frailty of salvation. One is certain; the saintly clothing of literature has been blasphemed by X-esque infirmity. Consider me the oracle of Vladimir Nabokov. One to spearhead the incantation of a testament, and the juxtaposition of Soyinka with the Nabokovian. Consider this an invitation to a beheading—A severing of philistinism from planet X.

The Black race’s solitary vanguard and Nigeria’s sole witness to the Nobel prize, Wole Soyinka, stands as the victim to a vituperative outburst as regards the verbosity and complexity of his prose from his countrymen in the social media platform, X(formerly Twitter). ‘Needlessly verbose’ and ‘grossly complex’ are the twin phrases to summarize the entire lamentation.

These laments, though borne of understandable fatigue in the face of Soyinka’s linguistic opulence, remain hidden in the blind spot of a shortsighted understanding of his genius. The density of his prose is no mere indulgence in the verbose but a masterful invocation, an invitation to the human condition, particularly the Nigerian condition and a romance with myth. To dismiss such craftsmanship, as an attempt at bombast, is to forsake the very marrow of his artistry, to shy from the profound engagement his works demand.

II.

Vladimir Nabokov, the great Russian-American novelist of the 20th century, believed that beautiful language was crucial to literature because it elevates the experience of reading beyond mere plot or message. For Nabokov, literature was an art form, and like any art, its success depends on its aesthetic qualities. He valued precision, texture, and rhythm in prose, considering the sound and structure of language to be as important as its meaning.

Consider the following excerpts from his essay “Good Readers and Good Writers”.

“There are three points of view from which a writer can be considered: he may be considered as a storyteller, as a teacher, and as an enchanter. A major writer combines these three-storyteller, teacher, enchanter but it is the enchanter in him that predominates and makes him a major writer.”

“To the storyteller we turn for entertainment, for mental excitement of the simplest kind, for emotional participation, for the pleasure of traveling in some remote region in space or time. A slightly different though not necessarily higher mind looks for the teacher in the writer. Propagandist, moralist, prophet-this is the rising sequence. We may go to the teacher not only for moral education but also for direct knowledge, for simple facts. Alas, I have known people whose purpose in reading the French and Russian novelists was to learn something about life in gay Paree or in sad Russia. Finally, and above all, a great writer is always a great enchanter, and it is here that we come to the really exciting part when we try to grasp the individual magic of his genius and to study the style, the imagery, the pattern of his novels or poems.”

In his view, without an attention to the form and beauty of language, a writer’s work risks becoming flat, didactic, or emotionally hollow.

Nabokov held on to his words as can be seen in the opening paragraph of his most famous novel, Lolita (1955).

“Lolita, light of my life, fire of my loins. My sin, my soul. Lo-lee-ta: the tip of the tongue taking a trip of three steps down the palate to tap, at three, on the teeth. Lo. Lee. Ta.

She was Lo, plain Lo, in the morning, standing four feet ten in one sock. She was Lola in slacks. She was Dolly at school. She was Dolores on the dotted line. But in my arms she was always Lolita.”

III.

Let’s now consider Soyinka’s first novel, The Interpreters (1965). A prose influenced by modernist literary techniques, particularly in its non-linear narrative structure.

Language was used diversely in this novel. There is lyrical prose, pidgin, and proverbs. Soyinka uses lexical, emotive and poetic meanings in a fusion to articulate and express his distinctive philosophical perspective. Several passages will serve to illustrate this.

1: “They embraced tables and chairs, pushed them deep into the main wall as dancers dodged long chameleon tongues of the cloudburst and the wind leapt at them, visibly male-violent. In a moment only the band was left.”

Here Soyinka describes a dance merging intense sensory experiences with rich symbolic meaning.

2: “Across the floor, an albino sat slanted like a leprous moonbeam without the softness. Freckles on his face like poisoned motes, dark scabs, and they floated on sheer phosphorence of the skin.”

Here, Soyinka employs imagery and simile, with precision, to create a striking portrayal.

3: In some passages, Soyinka employs humour.

“The “plop” continued some time before its meaning came clear to Egbo and he looked up at the leaking roof in disgust, then threw his beer into the rain muttering. “I don’t need his pity. Someone tell God not to weep in my beer.”

4: In some, he adopts the use of the African proverb, a feature more common in the work of his contemporary, Chinua Achebe.

“My boy, it never does to try your elders. When a cub yields right of way to an antelope, first look and see if Father Leopard himself is not a few trees behind.”

5: Then there are passages that contain unsullied lyricism.

“The rains of May become in July slit arteries of the sacrificial bull, a million bleeding punctures of the sky-bull hidden in convulsive cloud humps, black, overfed for this one event, nourished on horizon tops of endless choice grazing, distant beyond giraffe reach.”

Overall, Soyinka’s language in The Interpreters is an intricate, beautiful fusion of African tradition and modernist experimentation. A testament to his mastery of the craft and not merely an attempt at being “needlessly verbose” or “grossly complex”.

IV.

A writer ought not to dumb down his or her work for your comprehension. Rather, it is the responsibility of the reader to reach for their dictionary and embrace the challenge of understanding.

Certain emotions and portrayals of the human condition cannot be achieved without a certain degree of complexity in a work of literature.

“For me, a work of fiction exists only insofar as it affords me what I shall bluntly call aesthetic bliss… the sense of being somehow, somewhere, connected with other states of being where art (curiosity, tenderness, kindness, ecstasy) is the norm.” ~ Vladimir Nabokov.

Okigbo Makuochukwu (Contributor)