Women and the UI’ SU Presidency: Analyzing the Patterns and Perceptions

The phrase “women in male-dominated spaces” has dominated the online sphere for a while and even progressed to the day-to-day lexicon. Society often fixates on women who dare to step into leadership spaces traditionally held by men. However, this has not prevented women from occupying said spaces. It has even been a motivator for some. Yet, when it comes to the University of Ibadan’s Students’ Union presidency, women remain noticeably absent.

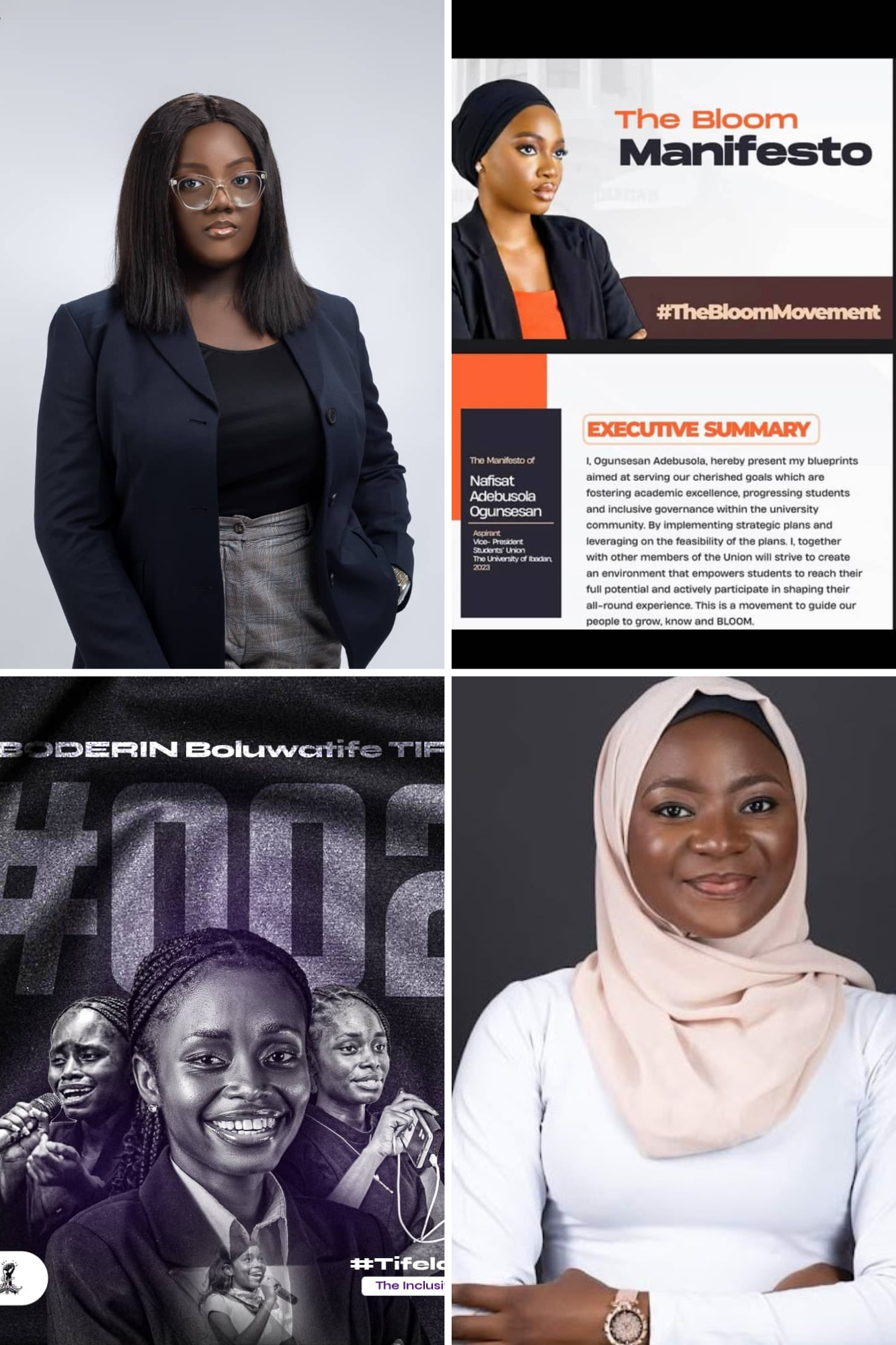

The Union has had a consistent stream of male presidents: this year’s Aweda, last tenure’s HOST, to Akeju Olusegun, Ojo Aderemi, and even Aliyu Olateju. On the other hand, the Vice Presidency has been a stronghold for women. The current Boluwatife Aboderin, former Nafisat Ogunsesan, Zainab Oluotanmi, and Oladiti Temilade Aisha have all underscored this pattern. While the president’s office remains untouched by female leadership, the second-in-command role seems more accessible.

In 2023, Adeyeye Bukola Shalom (ABS) attempted to shatter this status quo but fell short. Before her, the last female presidential aspirant was as far back as 2015—Toyosi Akinloye Grace. The statistics raise critical questions: Why do women shy away from contesting for the Union’s highest office? Is it societal bias, a lack of strategy, or mere disinterest?

Before diving into the discussion proper, it is crucial to understand the assessment of the issue through a broader lens—not as an attempt to argue about gender representation issues just for the sake of it, but to understand the causes of the imbalance, its effects on campus, and ways to correct it if need be. Leadership must, without question, be evaluated by competence and capacity.

Speaking on the matter, Nafisat Ogunsesan, the immediate past Vice President, emphasised that women should not vie for the presidency out of impulse or merely to address gender biases. “I would not expect people to follow a female candidate blindly because we are trying to correct a stereotype. That’s not an environment I would want to survive in” she explained. However, Nafisat also acknowledged the bias in society: “It is a structured bias to see the vice president role as a second-person role and generally ascribe it to women.”

The current Vice President, Boluwatife Aboderin, attributed the trend to a community bias. “From my perspective, everyone just knows their capacity and what they would like to do and simply go for it. Its being a trend, however, might be because of community bias of how it has been over the years“. On whether males are better suited to the SU presidency than females, “Definitely not!”

For some, the presidency is viewed as a high-stress role, deterring female aspirants. Others point to societal stereotypes and the perception that women lack the support networks needed to succeed in politics. “Males naturally detest having a woman tell them what to do” and “there’s a thing with females not being loyal to one another when it comes to power.” This perceived lack of solidarity and broader societal reluctance to accept female leadership can discourage women from attempting, creating a vicious cycle: women don’t contest because they feel unsupported, which results in fewer role models for aspiring candidates, further discouraging participation. According to veteran Campus Journalist and Editor-in-Chief of the Queen Elizabeth II Hall Press, Simisola Afolabi, “Whoever is vying for 001 needs to have a winning mindset, but most girls might feel it’s too competitive. Some girls might not contest because they don’t want to mess up, either. The VP duties, like planning health week, might come across as ‘for females,’ so they go for it. Being the president takes a lot and is a lot of work“. However, she affirmed her belief in the capacity of women to take on this role, highlighting the stronger political structures and influence in male halls compared to female halls, which might give male aspirants an advantage.

What happened to ABS?

In 2023, Adeyeye Bukola Shalom contested for the UI’ SU presidency against Samson Tobiloba (HOST). However, her candidacy was marked by significant lapses. With most students reporting minimal awareness of her campaign, it was said that she hadn’t gathered a strong enough influence to have run for such a strong position.

In UI politics, support from one’s hall of residence often serves as the cornerstone of a strong campaign. For ABS, this backing was noticeably absent. Beyond a banner reportedly hung at Queen’s Hall entrance, her campaign strategy appeared invisible to many. A respondent noted: “The executives didn’t really support her, Queen’s wasn’t behind her. So it was like a solo battle.” She “just didn’t have the social skills needed for such a position” which is apparently one of the things a hall considers before backing a candidate.

Her lack of preparation became evident during the Press night in which she scored 68.4 (3rd out of 4 candidates) and the presidential debate with a score of 54.1 (4th). Speaking with the Press, another resident says, “No hall will not back a candidate that has an 80% chance of winning.”

Although all efforts to speak with the former aspirant proved futile, we gather from her interview at the time with the UCJ under the Election Watch Room Program here that she claimed to have held her “room-to-room” campaign alongside an online strategy. However, concerns over the mode of collecting students’ data for this online campaign raised eyebrows.

Ultimately, her non-success was attributed not to gender but to poor strategy, limited influence, and lack of support. A respondent noted the stark contrast if someone like Nafisat Ogunsesan were to have contested: “Imagine Nafisat running for SU president after serving as VP—it would be one hell of a battle for any male contesting against her.”

Some even mention that Nafisat had quite a chance before running for vice. However, when asked why she chose the ‘2nd’ seat like most females have been seen to, Nafisat admits that her choice to contest for vice president was strategic rather than influenced by stereotypes. She noted that the VP role aligned better with her plans and schedule, as it allowed for greater impact. Her advice to aspiring female leaders is clear: “Know what you want and go for it.”

Breaking the Cycle

Although stereotypes do exist and, in subtle ways, influence the system, the emergence of a well-prepared female candidate could trump all that. Biases aside, respondents agreed that competency is the most important criterion for leadership, regardless of gender. They simply expect a good track record, strong qualifications, and, most importantly, a solid campaign. The self-perpetuating cycle due to the lack of female precedents might reinforce stereotypes that high-stress leadership roles are a man’s domain. Beyond the SU, this trend may send a message that spills into careers and broader aspirations. But this is easy to solve.

Aspiring female leaders must approach the SU presidency with the same level of preparation, strategy, and influence as their male counterparts. Nafisat advises: “Gather your experience, top up your qualifications, play the games, build your networks, get the money, and be ready to give it your all if you want it that bad. Fight your way, though, and show them the battlefield is what you need, not some extra favour or someone to ease it for you just because you are a woman. If you do, the battle will not be won regardless.”

Then, society must discard gendered biases when evaluating candidates. There are no “male” or “female” candidates, but simply competent or less competent ones. How we speak about the initial females who will dare to run will impact their campaign, no matter how good, and what really will be the point of a candidate giving their all to an already rigorous competition if we dampen it down to the presence of a y chromosome? The challenge lies not only in proving whether women can lead but in society judging purely by merit.

The University of Ibadan Medical Students’ Association is good proof of this theory of ‘cycle-breaking’ being a joint effort between society and women in politics. The now 64-year-old association did not have a female President until Jaachimma Nwagbara famously won her election in April 2022, running against a female candidate as well. UIMSAites looked beyond gender and towards capacity, and the aspirants as well campaigned with the fervour of one who sought to win, bias be damned. A year later, Odeleke Maryam would also win, this time against a male opponent, in a contest that ultimately came down to pure mettle.

Conclusion

Student leadership, in general, has always been a male-dominated space, and the history of the Students’ Union, in particular, mirrors this reality. However, breaking this cycle and encouraging female participation goes beyond slogans of “gender equality” or “women can do better” to an understanding that all women need to do is what past leaders -male or female- have done: show skills, strategy, and the ability to deliver. Also, the student community has to discard outdated notions of capacity being a gendered trait rather than an individual feature

Rodiyah Khidir