Disrupting the Status Quo: A Glance at the Creative Layi Wasabi

We’ve been made to believe that to thrive in any field, we must stick to the model others have used to become successful. I call it the conform-to-the-existing-model syndrome, and the Nigerian skit-making industry is not left out. The existing model is simple: satisfy the audience with exaggerated physical comedy, funny costumes, drama (lots of those) and to crown it, sound effects. Wait, another important thing, steer clear of smart comedy, they don’t appreciate clever entertainment, I mean they’re Nigerians. There’s always someone who disrupts the status quo. Someone who dares to be immune to the conform-to-the-existing-model syndrome.

‘Info lèyán fín fò’. You’ve heard this innumerable times. I vividly remember this phrase garnering prominence on Nigerian social media last year. Its prominence is justified given its brilliant play on words and the deep meaning the phrase exudes. This phrase is an extract from one of the skits of Isaac Olayiwola, popularly known as ‘Layiwasabi’ or ‘Layi’ whose works don’t conform to the existing model.

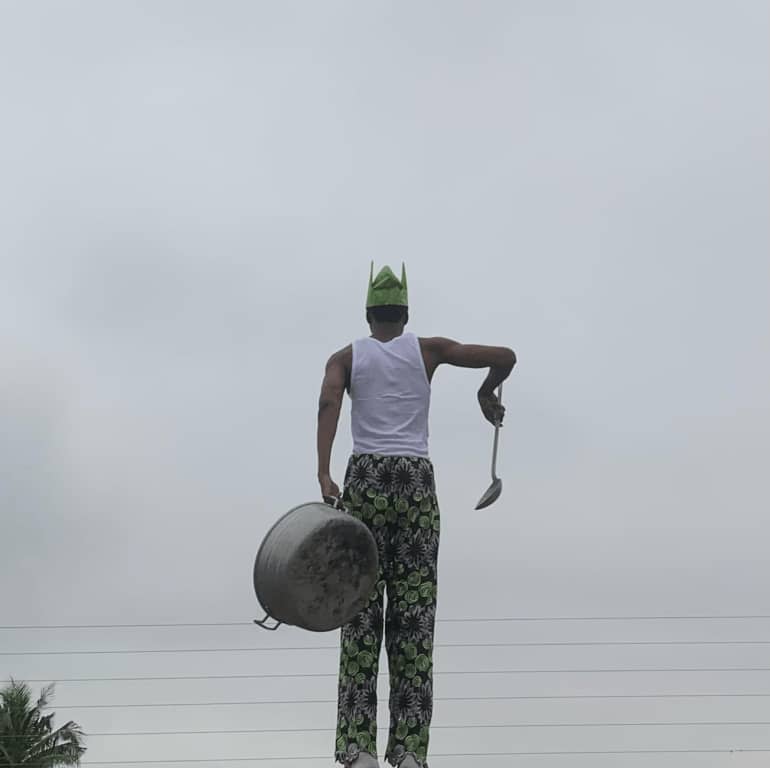

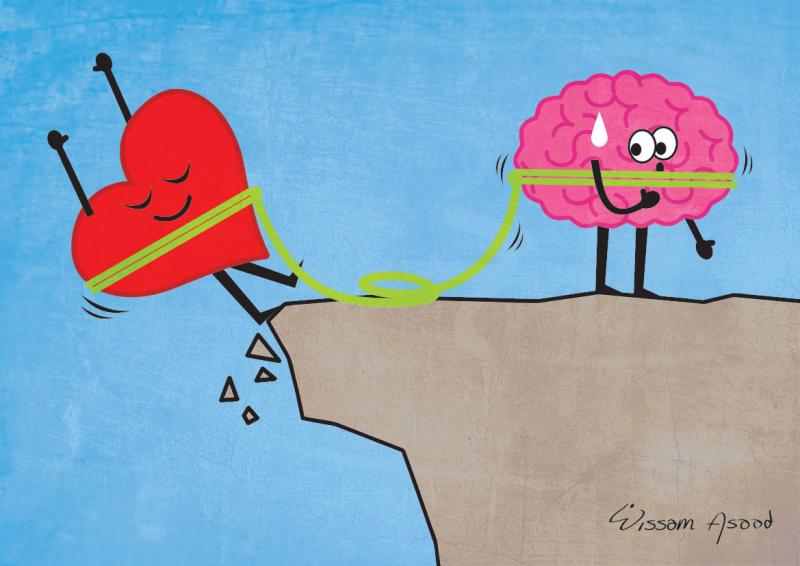

Layi is a 22-year-old graduate of Law whose 6’4” height makes him naturally stand out among other skitmakers. A giraffe amongst penguins, metaphorically. But it’s not just his height that makes him the cynosure of all eyes, it is his creativity. Layi has mastered the art of weaving the unusual with the familiar. He understands that both are fragile, and he must be careful when weaving them together to produce a beautiful piece. At the same time, he acknowledges that too much of the unusual would make his work outlandish to his audience and too little or none of it would make him just like the rest. The unusual is his use of clever comedy while ensuring he does not go over the top with it. Trusting his audience to be witty enough to catch the punchlines thrown at them, Layi has proved that the Nigerian audience is open to variety and the notion of Nigerians not appreciating clever comedy is arrant nonsense. The unusual is his avoidance of lewd comments and objectification of women in his skits, commonplace in the skit-making industry. Unusual still is his simple and short style of comedy. Layi’s skits are void of sound effects like ‘Funke’, ‘you’re a mumu man’ accompanying the work of many skit-makers. He can land his punchlines without the assistance of sound effects to hint his audience about the joke. At the same time, the comic knows how fatal the neglect of the familiar or too much of it would be. The familiar — facial expressions, physical comedy, funny costumes, and relatability are essential in communicating with his audience. Balance is the best way to put it, Layi Wasabi’s got plenty of that despite his gangly frame.

It’s little wonder he clinched the ‘Best Digital Content Creator’ award for his work, ‘Medical Negligence and Copyright Infringement’, at the recently concluded AMVCA. AMVCA (African Magic Viewers’ Choice Awards) is an award show recognising outstanding performance in TV, film, entertainment, and now in digital content creation within the African continent. Layi would go on to defeat Adebola Adeyela (Lizzy Jay) in ‘National Treasure’, Elozonam Ogbolu, Lina Idoko and Jemima Osunde in ‘Hello Neighbour’ and Apaokagi-Greene in ‘The Boyfriend of Maryam’.

Whether he’s playing the role of ‘The Law’, a struggling Nigerian lawyer with an ill-fitting suit from God knows what century, Mr Richard, who goes about convincing people to join his life-changing investment scheme or Mr Robert, the Policeman, Layi does a good job of entertaining his audience while also providing an insightful commentary on societal issues. He’s a testament that success can be obtained without following the existing model.

Eninlaloluwa Popoola

Wonderful writeup. It was captivating from the starting to the final word. Well-done to the writer! 🎉🥳

A well-written piece 🤗

Love it!