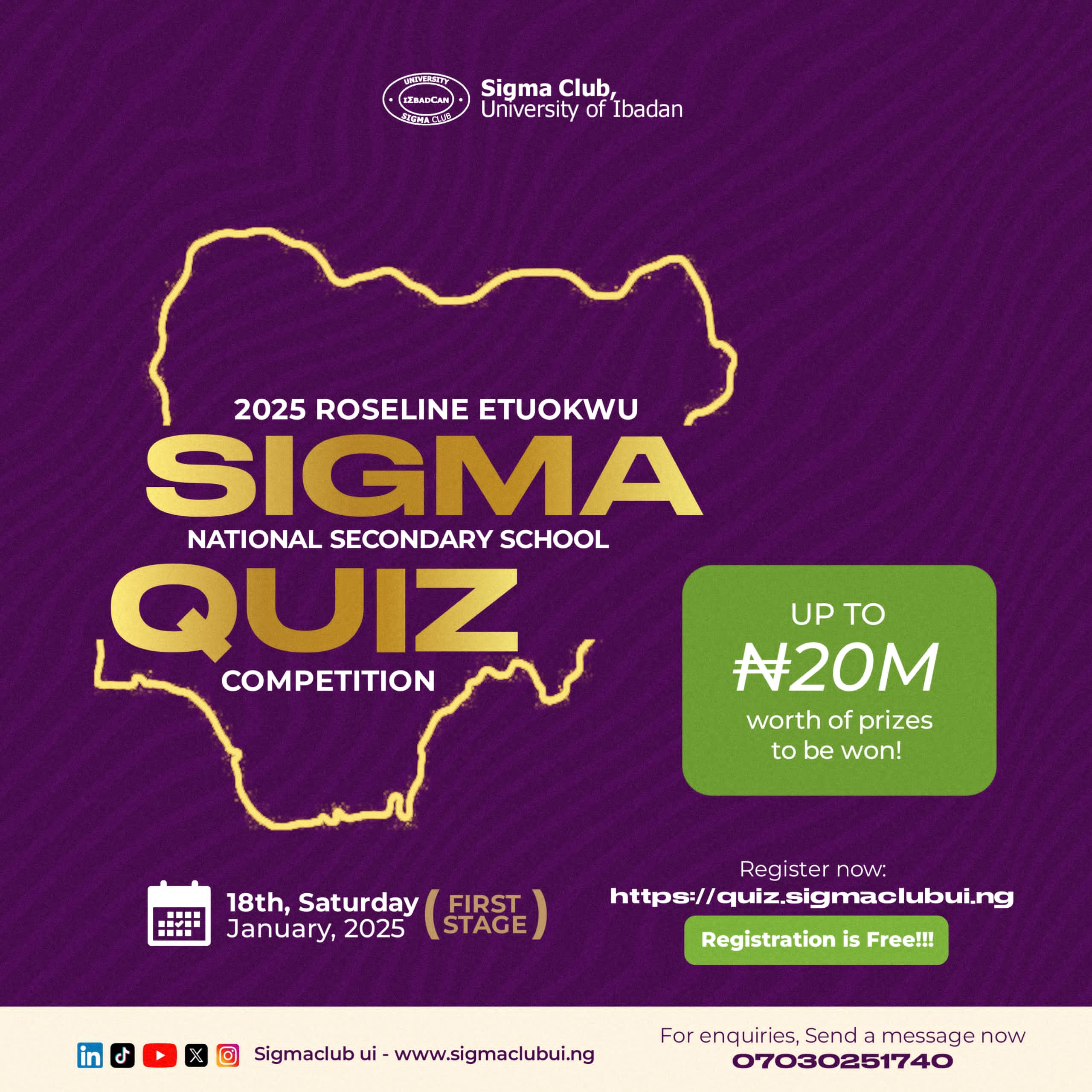

Sigma Club to Kickstart 5th Edition of Roseline Etuokwu Quiz Competition

The 2025 Roseline Etuokwu National Secondary School Quiz Competition preliminaries are set to be held on January 18th, 2025, as various secondary schools across the 36 states of Nigeria have been notified and prepared.

The competition, organised by The Sigma Club, will continue with the regional stage. Here, top schools from each state will battle other top schools in each of the six geopolitical zones. Subsequently, the top performers from each region get to battle for the ultimate prizes at the national level, at the University of Ibadan. These subsequent stages are to be determined at the later stage.

The rewards for the competition have increased substantially, with Twenty Million Naira worth of prizes up for grabs, as compared with last edition’s Ten Million Naira. Each state winner will walk away with 200, 000 Naira while regional winners will also get a reward of 500,000 Naira. The winner, first-runner-up, and second runner-up will get Five Million Naira, Two Million Naira, and a Million Naira, respectively, with 500,000 Naira consolation prizes each for 4th, 5th, and 6th national positions.

The Roseline Etuokwu National Secondary School Competition is now in its fifth year, beginning at the Intra-State level before scaling nationally. With over 1,300 secondary schools participating from the South-Western region and over 2,600 students, the competition is one of the Sigma Club’s major philanthropic activities.

Sidiq Moshood