Shelter Denied: Unpacking the ABH Accommodation Crisis

American psychologist Abraham Maslow listed shelter as part of the physiological needs in his Hierarchy of Needs, which are the most basic and essential requirements for human survival. Shelter, in this context, extends beyond just mere physical roofs but also includes safety, stability, and—within a school environment—the foundation upon which success—in this case, academic—can be built. Without it, students are left dealing with not only logistical inconveniences but also a greater feeling of displacement that can disrupt focus, well-being, and performance.

In the Alexander Brown Hall (ABH), accommodation of students has always been a complicated thing. But as we stand here today, in the aftermath of the 4-month-long MDCAN strike, these complexities have worsened into a cesspool of overlapping classes, delayed transitions, and increased uncertainty. And what we have left is a broken system. One that has stripped many students—freshman and sophomore clinical students alike—of what Maslow would call a fundamental human right: the right to shelter.

At the height of this crisis is the 2025 freshman class. Now, per tradition, freshers in ABH are guaranteed accommodation, as is seen in all other halls of residence in the University of Ibadan. But adding to that, this tradition is also very essential because the transition to clinical school is already difficult enough without forcing students to go look for where to find a roof over their heads.

But, for this class, this tradition has been denied. Due to a disrupted academic calendar and the presence of four overlapping clinical classes within the hall—a rare and unsustainable occurrence—many of these new students have been left without rooms. To make matters worse, due to the fact that these students assumed per tradition that they would be getting rooms, they did not expect or prepare for this occurrence ahead of time and were blindsided upon finding out last week, on the 6th of May, 2025, that they would be required to ballot for bed spaces.

And so, this class that’s supposed to start their orientation into clinical school in a week, on the 19th of May, finds themselves scrambling around, looking for rooms, seeking space in hostels outside UCH, navigating inflated housing costs, or commuting long distances.

This reality is jarring not only because it defies tradition but also because it exposes the vulnerabilities of a system stretched beyond capacity. In what should be a structured environment for learning, students are instead left to manage chaos, their academic focus clouded by the uncertainty of where they’ll sleep at night. And while some members of the 2K25 class were fortunate to secure accommodation, the majority were not—calling into question the planning and prioritization mechanisms currently in place at ABH.

“I had mixed feelings. A lot of my friends and colleagues didn’t get spaces, so it soured the joy.” – Joyce, 2K25

Joyce* is a female member of the freshman clinical class, 2k25. Upon hearing that their class would be required to ballot for spaces, she, like many others in her class, started house hunting. Fortunately for her, upon balloting. She found out that she was lucky enough to have gotten one of the few accommodation slots meant for her class. However, that joy was dimmed by the shared reality of her classmates. “It didn’t feel like my space again. I felt an obligation to share it with those that did not have it.” She said, speaking of the guilt that came with being one of the few lucky ones.

But beyond guilt was a deeper disappointment: in the institution, the process, and in the breach of tradition that should have shielded the ‘unlucky’ ones in her class from this chaos. “It wasn’t fair,” she said frankly. “We should have been informed earlier so we could prepare. And the 2023 class shouldn’t all have gotten rooms. Half should have been given to them and half to us. After all, we are both top priority here.” Her frustration is not misplaced, though. While ABH once guaranteed a baseline of structure, this year’s accommodation process was anything but.

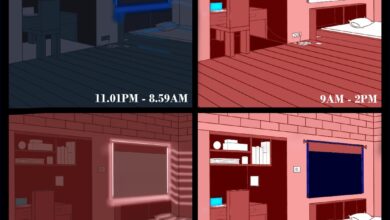

Other students in Joyce’s class, like Timothy*, were not as fortunate. “It wasn’t a good feeling,” he said when asked how he felt after finding out he didn’t get a room. There was no time to process the disappointment—only pressure to find alternatives. “There aren’t many apartments around UCH. You have to go all the way to Agodi or Bodija,” he explained. “And then there’s the high cost of total packages set by agents. It’s not easy.” The effects of this displacement go far beyond discomfort. For clinical students, mobility and safety aren’t optional luxuries—they are necessities. Postings often run into the late hours, and commuting long distances under uncertain conditions is not only stressful, it is dangerous.“ I particularly do not even like living outside campus because of the proximity,” Timothy added. That proximity isn’t just about convenience—it’s about security and sanity in a demanding academic phase.

Despite reaching out to the school authorities, Timothy said the response was stark: “Apparently, there’s nothing they can do at the moment.” It is a sentiment that echoes the helplessness many in the 2k25 class feel. “We are just new to the college,” he said, “only to get stranded from the beginning? That’s not really good.” And it’s not. Not when less than 10% of male students in his class reportedly got rooms. Not when tradition promised otherwise. And not when what should be a welcoming into clinical school instead feels like a rejection at the door. In both Joyce and Timothy’s stories, one finds a troubling narrative—the normalization of instability. A process meant to support learning has instead become a source of stress. A tradition once rooted in easing transitions now exacerbates them. And while some might try to make do, the question remains: At what cost?

But the 2K25 class is not the only one affected. While the freshmen suffer the brunt of the shock, the 2k24 class also has a very large percentage of their members having to go find accommodation outside campus. The only difference is that unlike the 2k25 class, these ones expected it. However, that does not make the situation right.

“Nonplussed. Unaffected. Meh. I didn’t expect accommodation in the first place.” – James, 2k24

James* is a male member of the 2k24 class. Like more than ninety percent of his coursemates, James balloted “no” in the accommodation ballot. However, unlike those in the 2k25 class, this is not James’s first tussle with the academic complexities in ABH. In 2024, when James was transitioning into ABH as a fresher. He, like many other students in his class, had to either commute from UI or find odd places to sleep during their orientation into clinical school. This was because the accommodation process for his class had not begun at the time of their clinical orientations, and the hall was still overwhelmed with students from older classes whose programs had been delayed. So, for James, the disappointment was familiar—almost expected. “Nonplussed. Unaffected. Meh,” he said when asked how he felt after balloting “no.” The words sound apathetic, but they are not. They are laced with the kind of resignation that only comes from having lived through the system’s failures more than once. “There is no dealing. Only acceptance,” he added later, when asked how he was managing the financial burden of alternatives.

The alternatives themselves? Bleak. “Squatting within ABH. Accommodations outside ABH. East 2 Ward,” he listed. “One is deemed illegal, though still a bit feasible. One involves hefty agent fees, stress, and transport fares. And for the last, the logistics aren’t so clear.” For James, none of them feel realistic. And private hostels? A fantasy. “They’re for the crème de la crème of society, the upper 1%. And as much as I would love to be a part of them, my financial capabilities keep my fantasies in check.”

There is humor in his tone, but it is the dry, sharp humor of someone who has learned to live with disillusionment. And it doesn’t end there. When asked how he felt seeing some of his classmates get rooms, his response was clinical: “This too had been expected… What they called divine intervention was nepotism in plain sight. Allegedly, of course. Only a fool would believe otherwise—and fools here are few.”

James isn’t the only one who thinks the allocation process this year lacked transparency. Derek, a member of the same 2k24 class who did get accommodation, admitted the process wasn’t fair. “Even my roommate didn’t get a space, so it hit me,” he said. “Most of the people in my class did not get spaces. I did, but I still do not believe it’s fair.”

Derek was already house-hunting with a friend when the ballot results came out. “It felt good,” he said, “because I didn’t even have the money to get a house outside. Getting a bedspace felt like a relief.” But that relief was quickly met with guilt. “It hurts seeing some of my friends in the 2k25 class struggle to get a bedspace,” he said. “Also, some of my classmates not getting a room this period would really affect them because of the incoming academic load. It wouldn’t be easy navigating accommodation issues with the daunting Block 2 lectures.”

Like others, Derek doesn’t deny that the situation was complicated. But he believes it could have been handled better. “They could have been flexible with the allocations, especially giving priority to the incoming students,” he said. “And for those who eventually ballot, it should be completely randomized.”

Randomization. Transparency. Affordability. These aren’t radical demands—they are the bare minimum for fairness. Yet, for many in the 2k24 and 2k25 classes, these ideals remain as distant as the hostels they now scramble to find. And yet, while the 2k24 and 2k25 classes are left to grapple with absence, the 2k23 class stands at the opposite end of the spectrum, caught not in the anxiety of not having, but in the quiet scrutiny of having too much.

“There’s no way I’m going roomless.” – Victor, 2k23

Victor is a male member of the 2k23 class, currently the final-year students in the college, and, unlike his 2k24 and 2k25 counterparts, he speaks with the confidence of someone whose place in the system is all but assured. And on some level, it should be. Because, around this time last year, his class was faced with the same accomodation challenges that 2k24 and 2k25 currently face. For him, accommodation should not really be in question. “I believe it has,” he said when asked if his final-year status helped secure him a room. “I’ve actually not checked the space to know who is currently occupying it, but I don’t think it would be a problem.”

His confidence isn’t baseless. According to Victor, his class was given a curated list of rooms to choose from—rooms not occupied by the 2k21 class. It was a process designed to avoid conflict, ensure clarity, and, more importantly, protect the housing rights of the outgoing 2k21 class. “So I don’t foresee that problem,” he said. “But if it does happen, the hall would have to somehow give me a free space, because I followed all the laid-down guidelines—and there’s no way I’m going roomless.”

For many in the younger classes, that sentence alone captures the disparity of the current situation. The certainty. The structure. While it didn’t last year, the system is working—for some. While others fight for scraps, 2k23 walks into rooms they were never really in danger of losing.

It would be easy to cast blame, but Victor himself is not the villain. However, he doesn’t even see the possibility of losing finalist status. “We will be the final year class until we are done, just as 2k21 currently is,” he said. “And just as 2k21 was given preferential treatment in room selection, I do not expect us to be treated any differently.”

And therein lies the quiet tension: one class operating under the rules of continuity, while two others are left to deal with the rupture of everything those rules once guaranteed. And in a year, even this arrangement might change. Still, Victor does not turn a blind eye to the systemic problems. “I’d like to praise the foresight of the immediate past Provost in kickstarting the new hostel,” he said, before urging the current administration to prioritize its completion. But even more telling is his suggestion on calendar reform: “The clinical school calendar should be adjusted to synchronize with UI, at least in approximation. Barring that, ABH should be run on a different calendar from other halls in UI to allow for the peculiarities of clinical school.”

It’s a recognition that the problem isn’t just about rooms; it’s about rhythm. About timelines that no longer align, traditions that no longer fit, and structures that are starting to buckle under the weight of exceptions and emergency patches.

Victor, like many in his class, has benefitted from the way things are, after previously suffering from it. But even he seems to understand that the way things are can’t continue. But long before 2k23 inherited the mantle of priority, it was the 2k21 class that laid claim to seniority—and with that, a complicated legacy of entitlement, exception, and unfinished exits.

“Anyone observant would have smelled it coming for over 10 months.” – Kenneth, 2k21

Kenneth* is a male member of the 2k21 class. Technically, his class should have exited the hall by now, but delays upon delays have left many of them still occupying rooms in ABH—rooms that could have gone to the students now stranded. And while Kenneth himself may not be directly affected by the current accommodation fiasco, he is painfully aware of the chain of events that led here.

“It’s a very sad situation,” he said, reflecting on the housing crisis. “And I cannot begin to imagine what each of the classes affected will be going through. For people not living in Ibadan, they essentially have nowhere to go. And even if they live in Ibadan, it will likely cost an arm and a leg to do this.”

For Kenneth, the signs were obvious. The backlog. The calendar. The compounding effects of a system that hadn’t accounted for disruption. “Anyone observant would have smelled it coming for over 10 months,” he said. And the four-month MDCAN strike? It only made everything worse. “The teachers did not have to be on strike for that long for their demands to be met,” he noted. “And one of its domino effects is what we are currently experiencing—amongst a number of others.”

His observations speak to something larger: a problem not just of housing, but of institutional foresight. For Kenneth, poor planning is the root of it all—not just the result of bad luck or tradition gone awry, but of decisions (and indecisions) stacked carelessly atop each other. And in the cracks of that pile, students are falling through.

Still, there are glimpses of hope. Kenneth praised the alumni body for their role in funding the new hostels, calling it “a testament to what students can do in the future when they are well catered to and taken care of.” But even in that praise, there’s a note of caution. “I’m afraid,” he said, “that many who have gone through the distressing experience in this session, compounded by many others, will lack the magnanimity to extend such contributions to their Alma Mater in the future.”

It’s a sobering thought. That the very students enduring these hardships now may one day walk away not with gratitude, but resentment. That the ripple effect of this housing crisis could stretch far beyond rooms and semesters, into the long-term relationship between the college and its future alumni.

And so, from every corner of this crisis—freshers and finalists, those displaced and those secured, those embittered and those reflective—one thing becomes abundantly clear: this isn’t just a failure of space. It is a failure of structure. Of planning. Of empathy. And it cannot be fixed by blame or tradition alone. It must be fixed by action.

Because while every student has told a different version of this story—of scrambling for hostels, of balloting into nothingness, of watching friends sleep on floors or pay through the nose for distant rooms—they have also all pointed, in one way or another, to what must come next. The next section is not just a conclusion. It is a call.

Some, like Victor, emphasize structural reform: “The clinical school calendar should be adjusted to synchronize with UI, at least in approximation. Barring that, ABH should be run on a different calendar from other halls in UI to allow for the peculiarities of clinical school.” It’s a proposition that recognizes the root of the problem isn’t just overcrowding—it’s a system trying to move two incompatible timelines in tandem and failing.

Others, like Derek (2k24), speak to the fairness—or lack thereof—in the allocation process itself. “The system wasn’t ideal. It should have prioritized freshers, and for those who ballot, it should be randomized.” Transparency, in other words, is not just a nice-to-have. It is essential if confidence in the process is to be restored.

Joyce echoed this sentiment from the receiving end. “We should have been informed earlier so we could prepare,” she said. “And the 2k23 class shouldn’t all have gotten rooms. Half should have been given to them and half to us. After all, we are both top priority here.” And in a sense, she speaks the truth. Because, while the 2k23 class is traditionally the final year class, they have no major exams coming up for the foreseeable future and already have most members out of UCH. Such a transition would have been easier for their class. Her proposal is simple: equity. Shared sacrifice. A return to balance.

For James, who found himself shut out entirely, the fix isn’t only about allocation; it’s about access. “There are rumors that the new hostel will open soon,” he said. “But there are also rumors it’ll be like the private hostels, only for the crème de la crème. It should be made affordable for all, and not for a select few.”

.

And Kenneth, though no longer on the front line, offers practical solutions from the rear. “The Carta lodge should be made available and affordable,” he advised. “Extra available rooms in Falase should be recruited. And to the general occupants of ABH—be more lenient. It is within your power to accommodate people who have no rooms.” These aren’t unrealistic demands. They are the collective wisdom of those who’ve endured the brunt of a failing system and are still willing to believe it can change. The call, then, is clear. Because shelter, as Maslow once said, is a basic human need. And in the context of a clinical student, it may just be the difference between surviving medical school and actually succeeding in it.

*names have been changed, upon request.