Here We Count Again!

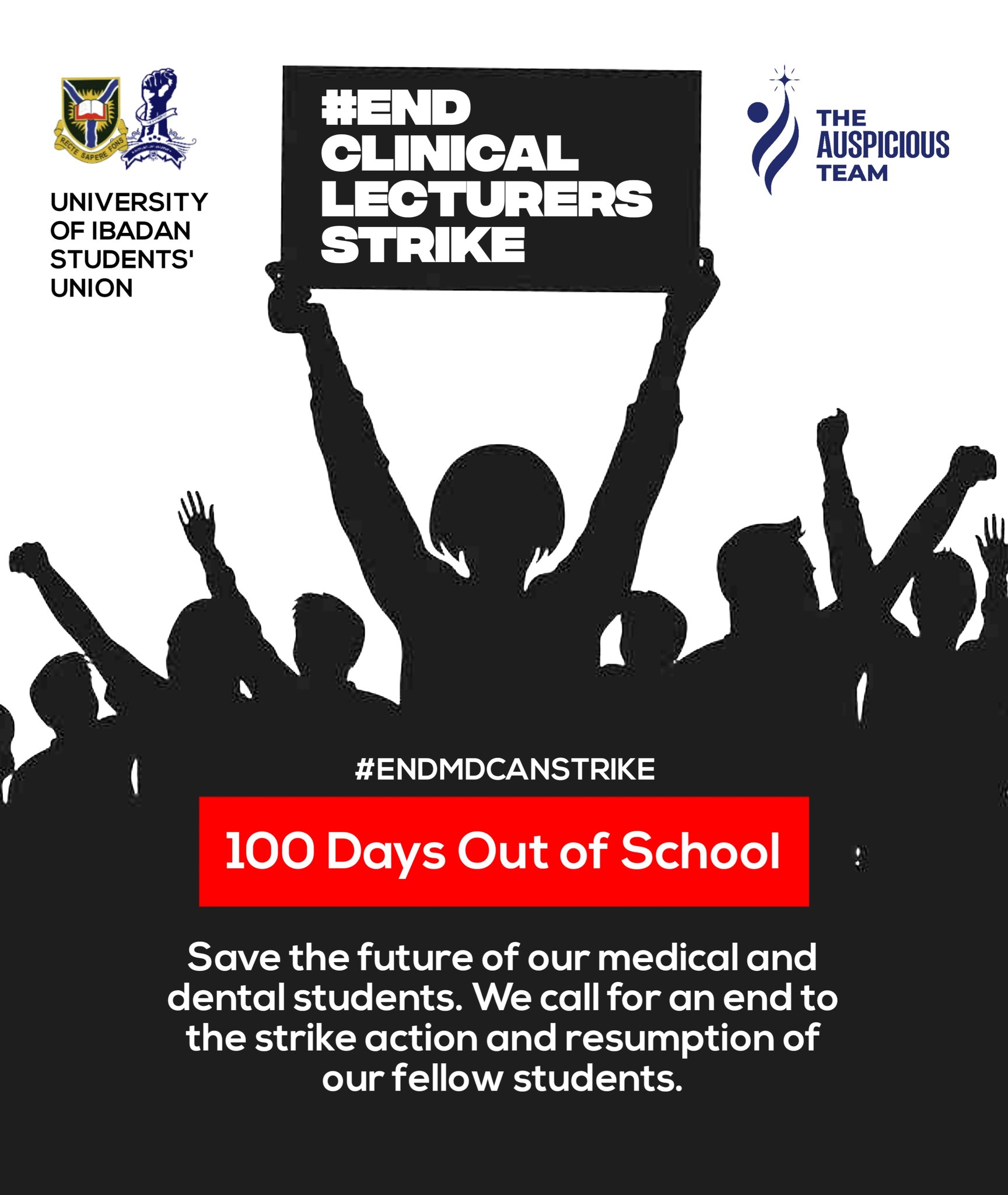

It is the journalist’s curse to write what few read, even when their efforts seem futile. From the litany of articles on the sprees of darkness in UCH/ABH to the numerous others on the political scene in UI and UCH, we have now begun to accumulate articles on another issue; the indefinite disruption that the Medical and Dental Consultants Association of Nigeria (MDCAN) UCH strike has wrought on our academic life. But in the words of our medical elders; “what is not documented, is not done”. In the same vein, what is not written, did not happen. And so as we mark another 100-day anniversary, we write again, if not for anything, to support our fickle collective memories with the ink of a pen, so that we would not one day find ourselves arguing how it happened, or whether it happened.

The 13th of December, 2024, happened differently for every medical and dental student at the University College Hospital, Ibadan. While some had had no intention of attending clinical activities from the get-go – in favour of searching for the nearest reliable source of water and/or electricity – others had gone to the wards only to get sent back by residents because “consultants are on strike”. Others still had a full school day; those rotating in units where the residents were not yet aware of the strike. But by midweek, the experience was uniform. It was puzzling at first since witnessing the oddity of consultants going on strike, but a welcome reprieve regardless. Very few had any information about why the consultants were on strike, and when they could be expected to resume. But in time, despite receiving no official information – neither from the College nor from the leadership of MDCAN UCH – students came to be aware (through rumours and secondhand conversations) that the strike was due to non-compliance of the university management with the Consolidated Medical Salary Structure (CONMESS).

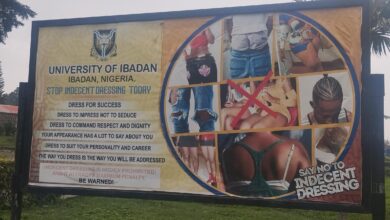

The Consolidated Medical Salary Structure (CONMESS) was approved in 2009 for all Medical and Dental Officers in the Federal Public Service. The Salary Structure which was to have taken full effect in January 2010 included specialist allowance, call duty allowance and teaching allowance, amongst others. From all indications, universities across the country adopted this structure except for Federal universities in the Southwest (University of Ibadan, University of Lagos and Obafemi Awolowo University) and the University of Ilorin. Presently, medical lecturers employed by the University of Ibadan are paid about 300-400,000 Naira monthly in contrast to their colleagues who are employed by the Hospital, or other universities in the country. Why these four are the only exceptions in a country of over 60 federal universities is a mystery, but the UCH branch of the MDCAN finally reached the breaking point and commenced an indefinite strike without prior warning. The branches in the University of Lagos and Obafemi Awolowo University downed tools about a month later. Since then, over a thousand medical students have been left watching and keeping count.

A Failure of Leadership

The problem with Nigeria is a failure of leadership

Chinua Achebe

Some truths are to be held self-evident. In the case of Nigeria, it is that leadership has failed, and continues to fail in a manner that is systematic and disgustingly present at every level.

The Nigerian government continues to show flagrant disregard for Health. The shameful number of dilapidated healthcare centres littering the country, the abysmal working conditions of healthcare workers and the bouts of darkness hospitals suffer as a consequence of sky-high electricity bills tell a tragic story that we keep lamenting. The Healthcare sector was allocated 5.18% of the 2025 budget – marginally better than in previous years, but a far cry from the minimum of 15% agreed on by the African Union. Of course, this did not stop the rolling out of several initiatives, the opening of new hospitals and the supposed upgrading of current ones. We are after all obsessed with optics. Tertiary hospitals continue to suffer from the lack of equipment, with doctors having to improvise at every turn. But only when things go awry, do citizens use social media to exercise their freedom of speech expecting doctors to perform miracles in impossible conditions. Resident doctors go on strike regularly, only to be forced to return to the same conditions that precipitated the strike. It’s no surprise that the Federal government under whom these lecturers are employed is unaware of how they are being compensated. It would be laughable if it was not so incredibly sad; their obliviousness towards the fact that over a thousand medical students have been forced out of school in the past three months. But this script is all too familiar. Perhaps the Federal Government is waiting for the strike to be brought to its attention so it can once again express shock and promise a shoddy band-aid solution.

The Education sector is not any different, if not worse off. In the guise of autonomy, universities have been left severely in need of funds. The ripple effect has been stunning; rocket-high school fees, students and lecturers alike living from hand to mouth, and an inability of institutions to provide basic amenities like water and electricity. The 8-month Academic Staff Union of Universities (ASUU) strike in 2022 is not so distant in memory. That all students enrolled in Federal universities in Nigeria were kept at home for eight months is mindblowing, even in retrospect. If students all over the country could be kept at home for so long; we can only worry how long this strike would last, considering that only three medical schools are affected. And since the consultants on strike are still attending to patients in the teaching hospitals, the Nigerian public is blissfully unaware and not incentivised to pressure the responsible parties into action. Yet again, the ball has been dropped to the bottom of the ladder for us students to champion the struggle.

This failure of leadership does not stop with the government. The universities also appear to be playing blind to a situation they are partially culpable in. There is a reason university lecturers are also referred to as Faculty. They are the driving force; the spirit within the University’s body. It is shameful that consultants who have spent decades in training and specialisation and dedicated their lives to passing on the knowledge and art of Medicine are being paid far less than entry-level jobs in the corporate world. It is even more shameful that these universities would refuse to remunerate their lecturers on a salary scale -which does not correspond to the amount of work being done by doctors – that has been approved nationally for 15 years, choosing instead to pay them arbitrarily. Not even the rapidly increasing disparity between the College of Medicine and the University of Ibadan’s calendar has hastened the management into addressing this issue. Medical lecturers at the intersection of Health and Education suffer the unique opportunity of experiencing failures in both sectors concurrently. But blessed are the medical lecturers, for they shall be paid double the reward in heaven.

At the risk of victim-blaming, one must ask why the leadership of the branches of MDCAN in these four universities were less radical about the plight of members for more than fifteen years. Even when MDCAN UCH decided to embark on a strike – an understandable course of action – there was no prior warning, no press conference, not even an open letter to enlighten the public about the situation. Medical students who bore the direct brunt of the strike were left guessing for days what the reason for the strike was. The communication chain appears to be broken within MDCAN itself, with the Southwest Zone giving a 21-day ultimatum several weeks after MDCAN UCH had already commenced its strike. The national leadership has mostly raised alarms over the situation, and medical lecturers at the College of Health Sciences, University of Ilorin, are still teaching despite being in the same situation as their peers in the universities on strike. This lack of coordination worsens an already terrible prognosis.

Structures and Sequelae

The University College Hospital was established to provide the facilities required to train the medical students in the just-established Faculty of Medicine, University College Ibadan after the 56th Military Hospital and Adeoyo Hospital were found unsuitable. Since it opened its doors in 1957, the hospital has provided healthcare to patients (at one time rated one of the top four hospitals in the Commonwealth) as well as undergraduate and postgraduate medical training. Teaching hospitals need to achieve a fine balance between training and service delivery. This balance is encapsulated in UCH’s vision: offering world-class training, research and services, and the first choice for seeking specialist health care. However, with the separation of leadership between the College of Medicine (headed by the Provost) and the Hospital (administered by the Chief Medical Director), this balance has been difficult to achieve. While we refer to the Hospital as the Laboratory for medical students, the relationship between the Hospital and the University remains testy. The Hospital has dedicated itself almost completely to patient care with little regard for what goes on with students. This disparity is so vast that consultants employed by the Hospital are paid almost double what those employed by the University are. Medical and dental students are familiar with being told to address their concerns to the University only to be faced with the University’s hand-off approach in matters occurring within the Hospital. In the most recent series of events, electricity was restored to the Hospital after the blackout only for students to find out that their hostel had been disconnected from the Hospital, even though it was the same students who had circulated hashtags and screamed themselves hoarse carrying placards for the electricity to be restored. When they were eventually reconnected, the meagre supply of electricity to the hostel was strictly rationed. Medical students bear the brunt of this imperfect structure, carrying the weight of anything that goes wrong on either side.

Just as a wide disparity exists between the College of Medicine and the University College Hospital, an even wider one exists between the College and the University. The University has been progressively shortening its calendar and overlapping sessions to make up for time lost during the COVID pandemic and ASUU strike. However, due to the peculiarity of the clinical training, its calendar cannot be compressed as each posting has a predetermined amount of weeks. This ensures that students get adequate exposure in wards and clinics, but it also means that lost time cannot be made up. For context, students admitted to study 5-year courses in 2018 have already completed their studies. Those in 6-year courses like veterinary medicine and pharmacy will be graduating before the end of the year, but medical students who matriculated in the same years will not be completing their postings until 2027, and that is if the current strike does not extend this date further. What used to be a 6-year course, now takes an average of 8-9 years due to incessant strikes. In a puzzling twist, however, the Alexander Brown Hall (ABH) follows the University of Ibadan calendar religiously, requiring students to pay (and switch rooms) at the beginning of every session without fail. Accommodation spaces that are already inadequate will be stretched even further, as more preclinical students complete their studies according to a compressed calendar while clinical students remain for an extended period. At the beginning of the next session, four classes will have to be accommodated in ABH as opposed to three as it previously was. If the MDCAN strike continues for a long time, preclinical students may have to wait at home for the better part of a year, before they begin clinical school to ensure that the class before them has almost completed 400 level.

The result is students who are already severely disillusioned with the system long before graduation. Housemanship and the National Youth Service Corps only add to this disgruntlement as they face the bleary reality of what it means to be a doctor in Nigeria. The mass emigration of doctors is nothing new, but an alarming trend is emerging, as medical students are now choosing to forego housemanship in pursuit of international licensing examinations. In the just concluded US residency matching program, two Nigerian medical students matched into residency in the United States before being inducted by the Medical and Dental Council of Nigeria. Fate must have a sardonic smile on its face, as the rate-limiting step for these Unilag students is for the strike to be called off so they can become medical doctors. We should interview former Minister of Labour and Employment Dr Chris Ngige to find out if he has changed his stance that the brain drain in the Health sector is not so bad as long as medical schools keep producing new doctors. It would be tolerable if it was only the bright-eyed and bushy-tailed new doctors who keep emigrating at an alarming rate. The truth is that on the planes that leave the country daily are medical consultants who have achieved specialist status leaving the country in droves to practise in saner climes. As if that is not enough, doctors are abandoning clinical medicine, pivoting to careers with better pay and work-life conditions. Those who have completed housemanship and NYSC are not even eager to begin residency preferring better-paying jobs to accumulate the funds for their exams and travel. Residency spots in hospitals remain unfilled and in a desperate attempt, hospitals have begun to employ residents without the preliminary qualifying exams by the West African or National College to bridge the loss of employees. Those who do choose to embark on residency in the country – either by choice or necessity – continue the cycle of strike actions for better conditions with no foreseeable change. Before long, Mama Doctor will not be the treasured title it once was and even the doubled academic quota in medical schools will not be enough to save our health in this country.

The elephant in the room is the collapse of public tertiary education in Nigeria, just like primary and secondary education before it. Since Igbinedion University graduated the first set of medical doctors in 2007, several private universities have been accredited for Medicine and Surgery. Those that can afford it, bypass the bottleneck of public universities and finish in the record time of six years. With Nigerian private universities ranking higher globally each year as public universities slink lower, quality tertiary education in a public institution in Nigeria may soon become a thing of the past. Students in public universities (still struggling to get basic amenities) would find it harder to compete with their peers from private universities, and almost impossible to compete on a global stage. Even when they go above and beyond to prove their capacities and break beyond their immediate environment, not many can afford the expensive process of exams, external postings and research positions to further their careers.

Picking up the Pieces

Aluta continua

Victoria ascerta?

For over 100 days, medical students have been left watching the clock, explaining to concerned parents, and responding to not-so-concerned neighbours why they are at home when everyone else is in school. As the 13th of December happened differently for every student, the strike is happening differently for everyone; some have watched movies to a mind-numbing point, some have found skills and talents to hone, while others have been sucked into the vortex of housekeeping or the hustle to feed themselves. What is the same for everyone is the feeling of helplessness and anxiety about what is to come.

Like #SaveUCH and #SaveABH, #saveourmedicaleducation now litters timelines and statuses as we muster what strength we can to bring attention to our appalling situation, hopeful that the public is not yet tired of us bringing one issue after the other for their intervention. We count day after day, biding our time until we are again forced to take to the streets to correct this injustice and demand that we be allowed to continue our education. But in our quest to be our knights in shining armour, we must not forget to question the people responsible for this in the first place.

The universities must explain why their employees are being cheated out of the payment prescribed nationally. The Federal Government must get to the bottom of why this mess occurred in the first place. If medical consultants are employees of the Federal government, it is its responsibility to ensure that they are adequately remunerated. MDCAN itself must pull its weight instead of waiting for someone else to fight its battle. The systemic failure in the Health and Education sectors must be addressed holistically otherwise these situations will continue to recur.

For us students, if we must win, we must present a united and consistent front so that our shouting voices are not lost in the void of everything else that is going wrong in this country. We must be loud and clear and relentless so that no one will have to ask us again “Are you on strike?” Hope is dead, but we must stay alive.

Congratulations to us as we break the 100-day record of dysfunctionality. Here we count again!