Reflections on Osofisan’s Vision of Soyinka’s Ìṣarà: A Voyage Around Essay

My generation of Nigerians suffer from poor attention spans. We also suffer from the decline of the educational system. In that regard, we’re disconnected from Nigeria in a manner older ones can’t quite relate to. Our hold on history is weak, as is our grasp on literature. The read-ones amongst us can sooner tell you about the colourfulness of Chimamanda’s Purple Hibiscus than any of the books in Chinua Achebe’s African Trilogy, bar the widely circulated Things Fall Apart. The most, most know of Soyinka is that he was the first African to win the Nobel Prize for Literature and that his recent politics are divisive. Don’t even mention the Clarks or Okigbos and any of the other great poets.

We’re knowledgeable, quite all right. At the University of Ibadan – the original Ivory Tower – the country’s brightest minds parade in shoes and sandals, always on the move and with a constant two-way stream of information: school and social media. It just so happens that these streams allow for minimal interference from channels like recreational literature. Plus, a level of conflict also exists within the current literary space. So, students barely have a reason to reach for this missing part of the whole.

This is one of a multitude of thoughts triggered in the wake of, and while watching, Ìṣarà, a stage adaptation of Wole Soyinka’s Ìṣarà: A Voyage Around Essay, at the iconic Wole Soyinka Theatre, on the 28th of July, 2024. As the audience gathered at the doors, I observed mostly students, expected given the location. The whole picture – gleaned upon interaction – is that this majority were students of the Faculty of Art. A representation of the state of recreational literature, among other things. There were a healthy amount of older folks, some strolling in with kids and discussing animatedly with one another. Call that the vestiges of a once vibrant Sunday afternoon culture. The harsh economy and fewer family-friendly spaces have resigned most families to evenings at home, recharging for the week for some, knee-deep into work for others. I’d like to think the absence of a gate fee helped a bit.

The play itself began with a seven-man prologue. All seven actors took turns describing the events that led Wole Soyinka’s father, Soditan ‘SA’ Akinyode (‘Essay’ in the title is a linguistic trick doubling as a familial joke. SA is Essay, you see), to the town of Isara. We were soon introduced to SA, or ‘Yode as friends called him, his elderly traditionalist father, Pa Josiah, and Sipe Efuape, his friend, a verbose Tax Inspector who has just returned from Lagos. Their jibes of Mr. Mephistopheles and Killer of Mozart were oddly familiar. After all, it’s an old formula: taking a highfalutin name and spinning it into something grand. In the larger departments, you’re bound to find these archetypes. When it’s not high language, it’s popular culture’s equivalent; Agba and Idan meet Odogwu.

The rest of the scene proceeds quickly. Sipe complains about ‘Yode’s insistence on staying in Isara rather than Lagos or even Abeokuta. He also decries the Doctors and Dispensers Association’s rejection of his herbal product. In the course of doing that, Pa Josiah returns. There’s trouble. Supporters of Ólisà, the unpopular candidate for the town’s chieftainship position, have taken to the streets. Pa Josiah explains that the kingmakers chose Saaki, another friend of theirs, but Ólisà, supported by a lone but powerful chief, Agbariku, whom Pa Josiah would later claim to have “too many memories“, rejected the decision and has since been causing trouble. This scene sets the events of the rest of the play into motion.

I was struck by the accent choice for the actors when this scene began. The actor for Pa Josiah (Tunji Aborisade) spoke with the Yoruba-accented diction adopted by Modern Nollywood in their depiction of the 20th Century-elderly, the ones who met the Brits but were simply too far along in age to imbibe both the language and the accent. While SA (Olugbenga Adekanbi) and Sipe (Atilola Omotehinse) mainly, spoke with an exaggerated colonial accent. Period-accurate as the accents were, it affected the clarity of dialogue. It also drew to mind conversations had in passing with older Nigerians and individuals in my age group. Both groups seem to agree on the inferiority of present-day accents (‘Accents’ because, contrary to Western portrayals, there is no Nigerian accent). However, the difference is the former long for the immediate post-colonial accent, while the latter prefer foreign accents, particularly ebonics and urban Black-British speak. That this points to a lack of identity goes without saying.

The play is set in World War II-British-occupied Nigeria, but the West-leaning behaviour of some of the characters would still find a place today. Not all of it is negative. In the second scene, ‘Yode and Sipe are in Lagos to meet with Samuel ‘Saaki’ Akinsanya and convince him to take his place as Ọdẹmọ of Isara. During the discussion, they reminisce about their days in the missionary school, particularly an incident involving corporal punishment. One of their classmates, Akanbi Berkley, who had just erred, tells Teacher that his father gave him a medical certificate to exempt him from beatings. To this, the teacher responds, “Did he now? But he forgot to give you some manners“, and flogs him a dozen times, citing tradition. The same scenario would play out in many of today’s secondary schools with no uproar. But not the majority. Private schools, especially, have adopted British and North American high school structures. Some have even incorporated foreign curricula. And parents would stop at nothing to ensure their wards are protected. Teachers, unlike Teacher, wouldn’t even dare the hassle.

Also in this scene are references to the politics of the times. Saaki, a former junior labour leader, was one of the leaders of the Nigerian Youth Movement alongside Nnamdi Azikiwe. But he lost a major election on the platform and believed Zik and some other Lagos politicians played tribal politics. It’s another oddly familiar coincidence. Having not read Isara myself, it’s hard not to wonder if this wasn’t Director, Professor Femi Osofisan’s way of addressing contemporary times or if it’s just a mark of how divisive Nigeria has always been that the politics of tribesmen has waxed more robust almost a century later. Elijah Adebayo, who plays Saki, sells his character’s anger at being cheated quite well. But not as well as he sells the look of comprehension when the reason for his friends’ visit finally dawns on him. Sipe is as amused as the audience is, saying, “It has made my day just to see you lose your power of speech“.

The following two scenes went by with little glamour. ‘Yode and Sipe return to Isara and relay the information of Saki’s acceptance to Pa Josiah. News trickles in that Ólisà’s men have murdered Pa Josiah’s friend, Jagun’s in-law. This escalates matters, so the duo of ‘Yode and Sipe hurry to Ibadan to meet another friend, Ṣotikarẹ, a lawyer. Unlike the duo, Ṣotikarẹ doesn’t believe Isara has anything to offer their generation. They eventually convince him otherwise, pitching the idea of an election at the Village Square. All three then leave for Isara.

Again, history plays a role in the outcome of events in the play. Pa Josiah is wary of Western dispute-resolution mechanisms. The duo mention how it worked with missionaries during the Kiriji War crisis with the Awujale, but Pa Josiah laughs, mocking their version of history. This dynamic carries on even today. It’s not exclusive to Gen Z — I assume you know my generation by now — as generations view historical events differently. Even with the litany of literature available in the aftermath of a June 12, for example, many my age spout skewed versions of events, tainted by the sources from which we read, watched or heard about these. Beneath the surface, there are those with seething, sated anger. Heated discussions at the Student Union Building Reading Room circa 2021 and on class WhatsApp groups, to name a few, spotlight the tensions that remain. Subtle but palpable. ‘My father told me that his father told him’s compete with Civic Education texts and thousand Naira paperbacks for a place of relevance. Schools do a poor job of connecting all of these dots. So, it’s difficult to explain how much nuance is lost and how it affects relations with others. Or maybe it isn’t; we have just learned to live with it.

I agree with Pa Josiah to an extent. Imperialism is a far-reaching, twisted thing. When Sotikare and Sipe sing, “Victoria, Victoria, àyè rẹ l’àwa ń jẹ/Ò sọ gbogbo ẹrú d’ọmọ ní ilé ayé wa”, a rough translation of which is “Victoria, we’re enjoying your reign. You turned all the slaves to children in our world“, I nod, humoured. How much freedom exists in the wake of the Empire’s exit?

Roaming thoughts meant I couldn’t catch the opening aspects of the next scene, the final one in Act 2. The Sipe and ‘Yode duo are back in Lagos, this time to meet Mme Santero, a Lagos ‘big woman’, played by an outstanding Segun Akinola. Mme Santero is a woman. Segun isn’t. So you can imagine how much laughter this brought the audience. His combination of a high-pitched accent and feminine mannerisms made for one of the more memorable characters in the play. Sipe makes her an offer. He would forgive her debt to him, and in return, she would provide one of her horses, a white Baia – named after her Brazillian roots. The plan is for Saki to ride into the Village on horseback. She agrees, and soon they set off for Isara.

The religious symbolism in this stood out. That this is a possible allusion to Jesus’ ride into Jerusalem — although on a donkey — isn’t so farfetched. After all, Soyinka is famed for incorporating religious themes into his work. In a review of Ìṣarà: A Voyage Around Essay by the Los Angeles Times from October 1989, columnist Carolina Slaughter says, “Here, Yoruba customs and beliefs lived side by side with the stiff teachings of Christian missionaries determined to silence the thunder of the pagan myths and rituals. Soyinka managed to take what he needed from both these religions, perfecting an even-handed communion with two cultures“. It’s an observation that holds water almost thirty-five years later.

The bigger elephant in the theatre was the dearth of female characters, with the lone one being played by a man. I attended the play with a female companion and she was not pleased by this absence. It was she, as well, who pointed out that Prof. Osofisan acknowledged this in his Director Notes. “Some will object for instance, to my decision to keep out from the story some of the interesting characters and in particular, all the female characters (except one, who is played however by a MALE actor). Such actions will be perfectly understandable. The only excuse I have is that, in this particular adaptation, and given the particular event I chose to focus on, the roles that such characters play are insignificant“. I agree that they [the female characters] weren’t significant in this particular adaptation. I disagree that they couldn’t have been written in some way. I especially disagree that they should have been written in for inclusivity’s sake. Prof. Osofisan’s other adaptations, like the seminal 2006 novel Women of Owu (from Euripides’ The Trojan Women), feature female characters central to the plot, making it evident that this was little more than a creative decision, the motives for which are best known to the playwright.

An interlude followed that scene. The trio were sent for, and what followed was the crowning jewel of the entire play. In a masterful display of third-act magic, we [the audience] bore witness to Jagun confirming Saki’s legitimacy as the Odemo of Isara. Saki was made into a medium for the Oba, conversing with ‘Yode and Sipe, the duo trying to convince him to let go and leave Isara in the hands of the man from Lagos. Elijah Adebayo, who played Saki, contorted and grimaced with the air of an aged man. His vocal alterations were equally imposing. As he recounted the story of the last time a town trusted in a young Lagos stalwart – the Ijebu case – and how it backfired, and how the missionaries were no more than emissaries of doom even though their god was called the Prince of Peace, the character of Saki disappeared even further. And not even after they succeed in convincing the Oba could I see him [Saki] the same way. Props to the Set and Light Designer, Alphonsus Orisaremi, and his assistant, Adebo Adeyemi, whose lighting fit the tone at every turn. And the Drummer, Abiodun Obadina, soundtracking like Stanley Okorie in the heydays of Nollywood.

Perhaps this feeling of euphoria made the final scene underwhelming. Saki, now Odemo, has snuck in to have fun with his old-time buddies. They reminisce about the good old days and the ‘ Et tu, Soditan’ story. And while that story instantly triggered a thought of the magic of percussion and why Afrobeats works so well, I was hard-pressed to ponder further—the story, done.

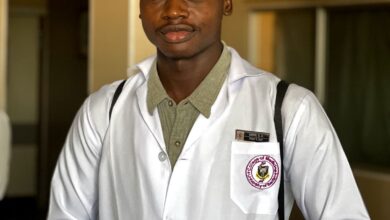

But nothing is ever truly done. Exiting from the theatre, two things occupied my head space. First, there is a gap in skill between theatre actors and regular actors. It’s little wonder why actors are advised to go through stage acting first and why the British continue to produce the best thespians on the planet – unarguably. The ability to make an audience of hundreds laugh for a two-hour run, like Atilola Omotehinse (Sipe) did, without multiple takes or guidance of an on-set director, is simply incredible. For all our complaints of stiff, emotionless acting, the answer might lie in the theatres, few and far between as they are. The second thought in my head was about writing this. How does a non-student of Soyinka write about Soyinka? How do you critique an art so far removed from your experience as a medical student? I found the answer in routine and Eniola Abdulroqeeb Arowolo’s essay, How Should One Read A Poem? Abdulroqeeb outlined the importance of Nigerian poets being better receptors to criticism. In doing so, he invariably highlighted the necessity of the critic and, thus, the necessity of the critic to be good at what he/she does. In summary, art appreciation can only be achieved by becoming one with art. So, I have to do that now. Consume more of these works. You should, too.

Dion