First, we will start with a little medical education. Heart failure is a complex clinical syndrome with symptoms and signs that result from any structural or functional impairment of ventricular filling or ejection of blood. To put it simply, it is end-stage cardiac disease, and is the natural fate of a host of cardiac ailments, with increasingly reduced capacity of the heart, that most-essential organ, to pump blood effectively to one’s tissues. Heart failure pharmacotherapy, or drug treatment, is defined by four primary pillars, that is the Renin-Angiotensin-Aldosterone System Inhibitors, Beta-Adrenergic Blockers, Mineralocorticoid Receptor Antagonists and Sodium-Glucose Cotransporter 2 Inhibitors. And without getting into the specifics of these drugs, one must know that they are the mainstays in Heart Failure management, although other drugs are often used as well, all dependent on the clinical presentation. Now, down that list of drugs could be our analgesics, or so-called painkillers. Acetaminophen/ Paracetamol/ Tylenol, whichever you know it by, is important in the management of chronic pain across a host of conditions, and in a medical landscape where pain management is becoming more and more focal, it is not out of place that patients be catered to in this way. But when this becomes less of medicine and more of juju or attempted murder, is when paracetamol becomes the centrepiece in the management of heart failure. When this becomes psychosis, is when we put a band-aid against a fresh amputation stump. And that, ladies and gentlemen, is the Nigerian government’s approach to healthcare and medical education in this country.

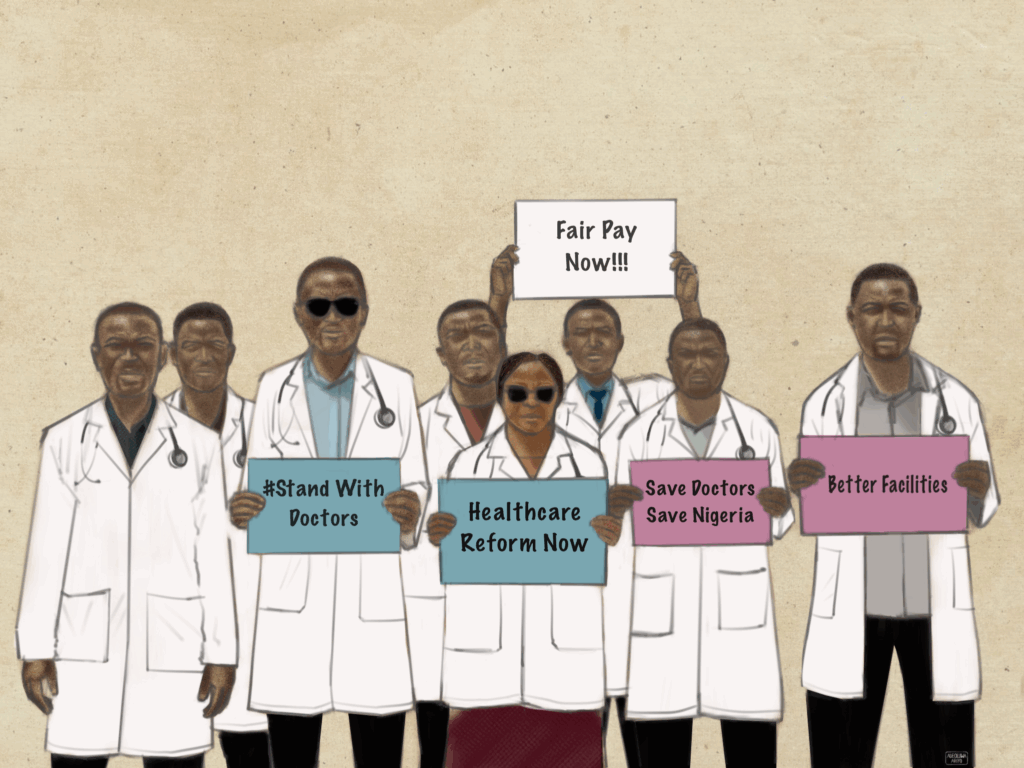

Across Nigeria, medical and dental education is collapsing: a nationwide landscape where students are stranded mid-training, programmes are suspended indefinitely, and entire graduating classes are left without pathways to induction. In LAUTECH’s College of Health Sciences, a convergence of labour crises has effectively frozen medical education. Since August 1st, 2025, the university’s medical lecturers under NAMDA and clinical lecturers went on an indefinite strike over the non-payment of the Consolidated Medical Salary Structure (CONMESS) and arrears going back to January 2025, and what they describe as discriminatory remuneration compared to other staff. The resident doctors went on strike as well, protesting the non-implementation of the new minimum wage for doctors, the withholding of the Medical Residency Training Fund, and crippling manpower shortages. With both the academic and clinical arms grounded, after the medical school remained shut for more than 100 days, medical students took to the streets and staged protests over the paralysis of their training. Now, the strikes continue, with no end in sight.

Just a few years earlier, a different kind of betrayal unfolded in UNILAG. For years, UNILAG operated a predictable pathway into medicine: students were admitted into 100-level science programmes with the understanding that, after their first year, those who met the standard CGPA requirement could “cross over” into the College of Medicine at Idi-Araba. But in 2016, the university abruptly altered the rules. Mid-session, UNILAG “changed the goalpost” by raising the cross-over cutoff to 4.11 CGPA, effectively disqualifying many students who believed they were already on track for MBBS. The administration defended the shift by citing indexing — a regulatory requirement limiting how many students can be officially registered by professional councils — even though this clearly mid-journey disrupted an academic pathway that had been stable for years.

A year earlier, in 2015, the University of Jos launched its 6-year dentistry programme, admitting 9 students. However, the programme was not yet accredited by the Medical and Dental Council of Nigeria (MDCN). Later, cohorts reportedly ballooned in size gradually, with the programme eventually accommodating hundreds of students, but still no accreditation. Graduating from a non-accredited program would mean a student has a medical degree but no path to a medical career, effectively rendering their education a wasted effort in terms of practising medicine.

By April 2024, the situation erupted. JUDENSA students protested publicly, drawing attention to the crisis and prompting the intervention of Plateau state’s governor, Caleb Muftwang. In June 2024, UNIJOS reportedly secured pre-clinical accreditation for the dentistry programme, clearing one of the preliminary stages required by the MDCN. Despite that, more than a year later and a full decade after the launch of the program, in November 2025, the pioneer class admitted in 2015 has still not graduated, owing to the clinical accreditation remaining unapproved, and no clear timeline for its completion has been communicated to students. The university is accused of intentionally admitting freshman classes into the program despite the lack of accreditation, without transparently disclosing the accreditation status at the point of admission, thereby misleading applicants and locking them into years of uncertainty.

On the 6th of November, JUDENSA members marched to the UNIJOS main campus gate, blocking access while carrying placards reading things like “Ten years, no graduation” protesting against their academic uncertainty. However, it was reported that they were dispersed by the police who used tear gas against them—a decade-long limbo met with violence instead of resolution.

A similar case was seen in the University of Calabar’s dentistry programme, where, despite the school insisting it holds valid accreditation, chronic over-admission has pushed the faculty into its own prolonged crisis. Despite an MDCN quota of just 10 students per session due to limited facilities, UNICAL reportedly enrolled far more, creating cohorts so large that by 2025, about 300 students had spent up to seven years in the programme without a guaranteed induction date. The MDCN openly refuses to induct a graduating class because the numbers far exceed the approved limit, and has threatened to suspend the program’s accreditation, causing a complete standstill for students. Now, over 300 students are directed to withdraw from the university or transfer to other institutions in an attempt to find a resolution, just like Ambrose Ali University’s 300 medical students were directed to sign an undertaking while sitting for their part 1 exams. This contract stated they had to enrol in an 18-month BSc programme in anatomy or physiology to stay occupied—while paying regular fees—because there was no available space ahead to proceed due to the college’s inability to induct the excess clinical students whose numbers exceeded the approved quota.

Overadmission just seems to be such a common thing in Nigerian medical schools now. But it is perhaps more ruthless in private institutions that do as they please and are driven to make as much profit as possible. Take Igbinedion University, for example, in which the first year medical class is swollen far beyond the programme’s realistic capacity, with fees positioned to attract a large cohort. But by 200-level, the class is abruptly trimmed down to roughly 150 students. Those who do not make the cut, even with exceptional GPAs—some as high as 4.9— are forced to either repeat the entire race the following year, switch to courses they never wanted, or perhaps change schools. This practice has created a breeding ground for ‘sorting’ in which students pay to secure their place, buy grades, or use influence to avoid being pushed out.

Fast track to current 2025 and we look at the University of Ilorin, in which the 25 of 175 newly qualified medical doctors, supposedly the bottom 25 by “ranking”, attended their University’s Convocation ceremony but were sharply excluded from their planned induction 2 days to despite passing the medical board exams because the university claims that the MDCN imposed a quota, allowing only 150 to be inducted. The entire situation garnered significant outcry, seeing that it could have been avoided with basic administrative discipline. The MDCN quota is not new; if the university had adhered strictly to the given limit from the outset, it would not have shepherded 175 students through six gruelling years only to attempt to discard 25 at the finish line. Even in the event of overadmission, the institution had a more preemptive and less unconscionable option: apply a transparent gradient curve enforcing rigour from the earlier years and ensuring that only the quota-compliant number progressed.

Across the country, these systemic failures place Nigerian medical students in a state of prolonged limbo, trapped in programmes that cannot guarantee graduation within stalling systems, thus deepening the psychological toll on students already studying challenging courses. And for what gain? At its core, much of this chaos is driven by selfish institutional incentives: the pursuit of higher revenue. Instead of prioritising quality and transparency, schools capitalize on student enrolment as a profit engine, leaving the very individuals who are supposed to become Nigeria’s future doctors stranded in a system that values their fees far more than their futures.

On the 1st of November, the Nigerian Association of Resident Doctors (NARD) once again embarked on an indefinite strike, forced back into industrial action after the federal government yet again failed to fulfil demands involving improved welfare, better working conditions, salary, among others. It is 26 Days in and in hospitals across the country, the consequences stare us in the face with elective surgeries suspended, overstretched consultants now bearing the weight of an already understaffed system and the education of students being affected.

Yet, amidst this paralysis, the 2024/2025 session draws to a close and the university expects a new set of doctors to train, despite the looming questions. Reportedly, in a bid to address the critical shortage of healthcare workers in Nigeria arising from the mass exodus of professionals, the federal government has apparently increased the quota of admission into 41 fully and 7 partially accredited medical schools in Nigeria by 100% . This was contained in a letter from the registrar of the MDCN, T.A.B. Sanusi, and addressed to the Secretary General, Committee of Vice Chancellors of Nigerian Universities, dated January 22, 2024.

On paper, the justification is simple: Nigeria needs more doctors, so universities should admit more students. But where? This logic collapses once placed against the reality of medical training in the country. The decision would be commendable if the system wasn’t already strained with cracks visible in university teaching hospitals across the federation.

In Ibadan, the conversation shifts from over admission. Unlike many institutions drowning in numbers they were never permitted to take, the University of Ibadan finds itself asking other questions: MDCN has raised its quota, and UI is preparing to admit roughly 350 medical students per set. On paper, this is legal. But legality is not the same as feasibility.

And in analysing this conundrum, we must first consider the effect of the recently concluded MDCN strike on the COMUI calendar. It is no news at this point that since students in clinical training at UCH were affected by both the MDCN strike and the UCH blackout which saw their education stall while their counterparts at UI carried on at an accelerated pace, today, the picture of years spent by medical students and non-medical students in UI is vastly different. The case of the recently inducted Class of 2025, Insignis will be news to many at UI, the fact that this class paid a seventh hostel fee at the start of this session as they strained to complete their degree well past the allocated time. And while they were able to attend the same Convocation as their counterparts in six-year courses on the main campus, such as Veterinary Medicine, subsequent sets will not be so lucky. This issue can be traced back to not only UCH-specific issues, such as the MDCN strike, but to the University of Ibadan’s decision to shorten her semesters from thirteen to eleven weeks in the aftermath of the 2020/2021 ASUU strike, in order to accelerate a stalling calendar. This change was never able to take root in UCH clinical training, where students face one of the hardest undergraduate workloads worldwide. To shorten it anymore would have been to compromise on medical training, and things continued as they were, unencumbered by decisions on the main campus. But now, we have such a disastrous picture that, while UI identifies a 600L Medicine and Surgery Class, that class is yet to even write their third Medical Board Exams, and are only projected to graduate in 2027. In contrast, their mates in six-year courses are rounding up their final examinations at the close of this year. The 500L class as well is in the same conundrum, with a graduation date set for 2028, staying in school well past their mates, expected to spend up to eight sessions as University of Ibadan students. With the same picture further down, and with the College of Medicine only able to induct one set of medical doctors per year as far as MDCN regulations are concerned, it becomes obvious that we are in a special sort of pickle, with UI graduating two sets almost every other year, owing to their speedy calendar.

One can argue based on this that what our medical program at the University of Ibadan needs at this point is a hold on admissions, rather than a ramping up of intakes. With the 2k26/300L class just completing their MB1 Exams, there are set to be four sets in clinical training at UCH, a number that will rise to five at the end of 2026. There is much to consider already with the arrival of the 2k26 class, when a number of 2k25 students still do not have accommodation in Alexander Brown Hall. And for all the talk on the College of Medicine Alumni Hostel, nothing seems forthcoming on that front, with no talk of an opening date, and even an apparent stalling in construction. It is simple—this school already struggles at caring for her present number of students. So what then is to be done when the number shoots up drastically? If we were to indeed go ahead with admitting up to 700 medical students over the next two admission cycles, whatever infrastructure we have will collapse under that burden

With UI marching ahead and admitting 350 medical students per cohort, the strain on its human and material resources will be severe, even with the brainpower deficit. Taking a look at the preclinical arm, the Anatomy department went from twelve to eight clinician lecturers, with current staffing levels only just sufficient to manage the existing body, not to mention a class twice as large. The Physiology department has only one lecturer with a core medical background, out of eleven, and even she is concurrently appointed in UCH, with the rest of the staff already splitting their capacity between medical students and their own BSc and MSc programmes, effectively making medics second fiddle. And even worse, the biochemistry department has no clinicians on her roster. And yet, the 16 teachers are stretched thin between external appointments and their primary obligations to Biochemistry majors.

Then there’s the equipment and facility pinch. In a system in which several students share a microscope and practical sessions have to be repeated in groups, pushing in twice as many students would only raise more questions: will they get more cadavers? How many students per microscope? How many practical groups and how many sessions per week? Will the anatomy lecture theatre accommodate the cohort, or will they have class arms now with different class times? Essentially, the facilities will be shared across a class size that it could barely cater to when halved.

On the clinical side, this is where the Nigerian medical-education pipeline collapses most visibly, because capacity at this stage is fixed in a way that admissions numbers are not. Ward rounds that should teach turn into silent processions because 30 students cannot meaningfully interact with one consultant or one patient. OSCEs and case-based assessments also lose their integrity when departments lack enough examiners or patients for standardized evaluation. Rotations depend on patient load, consultant availability, theatre space, and the number of clinics that can accommodate students. These are not expandable simply because quotas have increased. Medical education here is already in such a sorry state here when at two different junctures recently—the UCH blackout and the NARD strike now, students have undergone clinical rotations at points when the hospital had already discharged most patients, owing to the prevailing crisis. Let that be clear—there are students in UCH on clinical rotations currently surveying empty wards. The A&E is barred entirely, with no new intake of patients. William Osler cautioned against this when he said, “To study the phenomena of disease without the books is to sail an uncharted sea, while to study books without patients is not to go to sea at all.” And yet here we are, deceiving ourselves that we claim to learn without patients, the very focus of our practice. And now, in a situation where students should really be sent home while the government gets their act together, rather than twiddle their thumbs and stomp through empty halls, that same government intends to overwhelm this failing system and feed hundreds more students into it.

It is emblematic of the Nigerian way of handling problems. Rather than fix brain drain by treating the National Association of Resident Doctors’ concerns with respect, the Federal Government chooses to simply admit more medical students, the majority of whom would still become disillusioned with a failed healthcare system and seek to either leave the country or leave clinical practice entirely.

After clinicals, the housemanship crisis becomes the final and most damaging choke-point, because even after surviving six years of school and passing the MDCN exams, a graduate cannot be licensed without completing a one-year internship. The number of accredited housemanship slots, however, is not growing at the same pace as the number of medical graduates, as MDCN’s own published lists show that most teaching hospitals and federal medical centres offer only a limited number of positions per cycle. This leaves hundreds of new doctors each year stranded in a queue, some waiting six months to a year for posting, erasing the continuity of training and pushing many to leave the country immediately after induction. An expansion of admission while internship capacity remains static will simply lead to a backlog of newly minted doctors with nowhere to train.

If quota increases become the new national strategy, we must then ask: to what degree does each additional student further dilute the quality of education? Even for a university like UI–consistently ranked among the strongest in Nigeria and historically regarded as a benchmark for medical training—the standard is already strained by systemic factors: outdated infrastructure, insufficient staffing, overcrowded postings, and chronic underfunding. Excellence cannot be expanded by decree; it requires resources, stability and strategic capacity building. Hence, an increase in a cohort intake without a proportional increase in facilities will inevitably lead to a proportional decline in training quality. Increasing the quota in isolation will not strengthen the system but simply crush its already fragile body.

In teaching hospitals already grappling with stagnant education, chronic understaffing, delayed payment, ageing infrastructure, and nonexistent welfare, resident doctors who form the backbone of hospital service delivery are currently on strike over conditions that have remained unsolved despite repeated negotiations. Increasing admissions in this context, adding more bodies when capacity has not been strengthened, produces congestion. It is like pouring more water into a cracked vessel, simply deepening the fractures in a system already struggling to bear its current weight, and in fact, only further exacerbating the problem: a system from which doctors leave due to its inefficiencies, why would more doctors remain in? There will only be more doctors to japa. UI doctors themselves rarely remain within UCH for or after housemanship; many don’t practice in Nigeria at all. So what does it mean to expand production of doctors inside a system that cannot retain or absorb them?

In a state with not enough jobs for those trained, what other solution looms than to find pastures elsewhere? According to the Nigerian Association of Resident Doctors (NARD), nearly 19,000 doctors have left Nigeria in the past 20 years, with 3,974 departures in 2024 alone with the intention to migrate at a staggering high: as many as 85% of NARD doctors have expressed plans to leave Nigeria for greener pastures overseas not just for the lack of jobs or pay however, but also due to the lack of meaningful infrastructure, poor working conditions, and no real incentives to stay. The problem is not and has not been that Nigeria does not train enough doctors; it is that the very system that trains them gives them every reason to look elsewhere.

All of these cracks in Nigeria’s medical-education system feed directly into why NARD has gone on strike and what it is they are fighting for. Its current action isn’t just about money but demand for a system that can actually sustain doctors and retain talent. NARD has laid down 19 minimum demands, including full payment of outstanding CONMESS arrears and the 2024 accoutrement allowance, equitable salary corrections, enforcement of the “one-for-one replacement” policy so that doctors who leave are immediately replaced, and working-hours reforms are aligned with international best practices, among others. Crucially, NARD rejects superficial “fixes”: they insist on binding, time-bound commitments, not just press statements or vague committees. In other words, what they, we, are asking for is not charity but a functioning health-training ecosystem – one that doesn’t produce doctors only for them to leave or be destroyed by burnout.

At the end of it all, the crises rippling through Nigeria’s medical schools are not isolated accidents – they are symptoms of a health-training system on the brink of collapse. From the over-admission scandals to the abandoned clinical postings, every failure present mirrors the very conditions NARD is fighting against, the bare minimum it begs for to keep the profession functional. Because essentially, residents protesting burnout, dangerous workloads, and hospitals without functioning equipment, echoes the same reality medical students face when they queue for limited microscopes, miss clinical postings and spend years waiting to be certified doctors. And until we build a system capable of training doctors well – and keeping them — expanding quotas is nothing but an illusion of progress, worsening the very decay we pretend to solve.

It is our sincere hope that these empty measures, seeking only symptomatic treatment at best rather than addressing the root cause of this affliction that is Nigerian healthcare and medical training are abandoned in favour of definitive treatment strategies, aimed at restoring healthcare, in some way, the very lifeblood of the Nigerian people, to a state in which it can be once again, responsible to this population. And for as long as our doctor-to-patient ratio remains in the range of 1:8,000-9,000, well below the WHO-recommended 1:600, all operating in a significantly dysfunctional system that sees doctors, especially those in government-owned hospitals, improvise to embarrassing degrees to ensure that anyone gets treated at all. But for now, cardiac remodelling is a long time away.