How Brownites Have Adapted To Electricity Rationing Post 109-Days Blackout

On the 16th/17th of July, 2024, students of the University of Ibadan marched out to protest several displeasures catalysed by a memo stating a new electricity distribution schedule across campus, which the university management has refused to take responsibility for its release till date. After denying the release of that memo, they followed up with adequate power distribution most noticeably in hostels where students reside – until they didn’t. Slowly and diplomatically, the school reverted to distributing power for the number of hours (10) as the memo stated. In their crooked way of achieving the said aim, they did not follow the schedule religiously but ensured to fulfil the stipulated number of hours per day.

Here at the University College Hospital, after a 109-day blackout specifically in Alexander Brown Hall, residents had their bulbs back up and working. Still, they only light up for a specific number of hours daily. There was no formal notice of a new normal or schedule, and how long it would last, the residents just had to figure out the new schedule themselves and bend their routines to fit into maximum productivity in a situation ridiculously lower than the bare minimum.

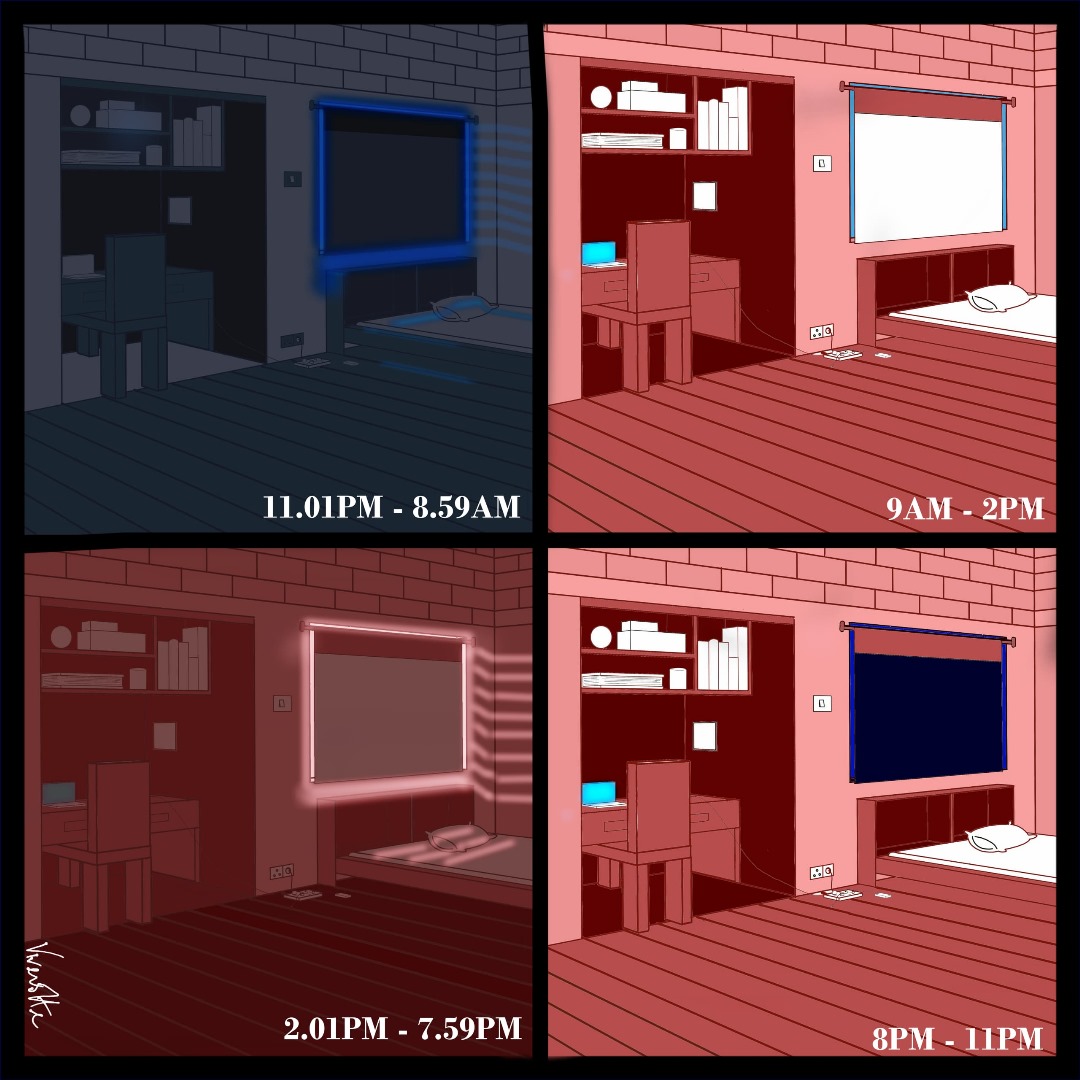

Alexander Brown Hall now gets lit up for only eight hours per day; a 5-hour supply from 9am to 2pm and a 3-hour supply from 8pm to 11pm. While much is left to be desired on the consistency of this yet abysmal new normal, what is more important is the stories of these students who have had to continue their medical education through this.

On evenings when electricity comes on as expected, Ibukun, a medical student, makes sure she charges all her devices and irons her clothes for school within the 3-hour window. This is because, like many other medical students, Ibukun does not get to use the light from 9am to 2pm as she would almost always be in school during those hours. “I usually don’t get to use the light from 9am to 2pm if I’m in school all day except on Saturdays. So I leave my devices plugged in before leaving for school. All except my laptop.” she explained.

Ruqayyah, a Medical Laboratory Student in her fifth year, also relates to not being able to use the light from 9am to 2pm. Just like Ibukun mentioned, she said “I mostly settle for the 8pm-11pm schedule as I’m always in school between 9am and 2pm. I come back around 5pm, wait till 8pm to press my clothes in preparation for the next day and to charge my gadgets.”

For Olamide, a final year medical student who also does not get to use the morning schedule light as he is expected to be in school, he also does not get to use the evening schedule light maximally because he has tutorials on alternate days, which last north of 2 hours during that period. According to him, the most he can do whenever he is around is to charge his devices. “Most times, I just plug down my powerbank and lamps when going to school with the hope that they’d charge before I get back,” he added.

While Ibukun, Ruqayyah, and Olamide communicate what the majority faces with the morning schedule, Osimenwu, a Physiotherapy student, represents a few outliers who don’t really feel affected by the 9am-2pm schedule. In a conversation with her, she said, “I don’t really have classes in the morning except for Mondays and Tuesdays, so the 9am–2pm light schedule doesn’t affect me that much most days.”

Save for a few outliers, the 9am-2pm light schedule does not favour the majority who stay in ABH. This speaks to the level of disregard the college has for its students when implementing such electricity schedules. But more importantly, it explains the reason many have had to find alternatives to maximally utilise the light when the hall is powered or source alternatives outside the hall if they can’t afford alternatives to save power when they are not around.

For someone like John, a medical student in his penultimate year, he makes up for missing the morning schedules by going to the E. Latunde Odeku Medical Library. According to him, “The 9am-2pm schedule is something I hardly ever use except on days where I do not have school in the morning.” “If I don’t iron my clothes or charge my devices the evening before, I can’t make use of electricity in the morning, so it is a real hassle,” he added.

Ruqayyah makes up for missing the schedule by dropping her solar lamp outside every morning or packing her gadgets to charge at her department. “I drop my solar lamp outside every morning to be able to use it in the night when light doesn’t come as scheduled or after 11pm when the light might have been taken,” she said. Osimenwu, on the other hand, does not have any solar gadgets but depends on a power bank that lasts very long and only resorts to charging at her department when it’s been off for too long. In extreme cases and for more convenience, Osimenwu stays back in the hostel to use the light even if it means that she misses a class. As inconveniencing as that sounds, it’s only worth it on days when this light comes on – and stays on – as expected. On some days, light comes on by 9am and goes off an hour or two later, making staying back not worth it.

Olamide finds solace in the solar hub in the TV room or Caritas when light fails. “If there’s no light, I make use of the solar hub in the TV room or I pay at Caritas opposite Accident and Emergency to charge my power banks,” he stated. For some students like Ibukun who do not have a safe haven in UCH, the alternative when light does not come on as scheduled and the blackout lasts more than 20 hours is to leave school to charge. According to her, “alternatives for charging would be to go outside school, as far as Bodija.”

Similarly, Ore, who is a final-year dental student, has had to leave school to charge when the going got tough. In a conversation with her, she said, “I think I have gone to my aunt’s place at Bashorun to charge one particular evening, because I was working with a really crazy deadline.”

John, who relies on the medical library, finds it a worthy option even on busy days. When asked how he navigates such days, he replied, “The library is really worth it for me. Even when postings are tasking and we don’t finish until 5pm, the 5pm-7pm window in the library helps a lot before I come back to use the light that comes on by 8pm.”

Even as many expect the conventional school hours to affect just the 9am-2pm light schedule, some postings rob students of the chance to utilise the evening 8pm-11pm schedule. On a few occasions when John was in Radiology, being on call deprived him of using light at night in the hostel. “Due to the electricity issue, I had to be on call from 8pm to 11pm because that is when the hospital will have power, which would allow us to observe procedures,” he explained. Gerald, a classmate, also relates to the situation when he’s on call in Surgery and he’s out in school until late in the night.

For the majority, it is dependence on heavy power banks, not-so-tasking school schedules, plugged gadgets in extensions, and neighbouring hubs that keep them connected. For the minority with heavy electricity needs, going out of their way to get expensive power stations has helped them thus far. Speaking with Gerald, a fifth-year medical student who bought a power station that serves his two-man room, he’s been at peace for the most part and he doesn’t really care if light comes or not. When asked if it has been worth it so far, he replied “Yes, it has been worth it, if they bring the light, it’s fine; if they don’t, it’s also fine because I always have power and should be able to do whatever I need to do.”

Unlike Gerald who had to spend his money on a power station, Ore was lucky to have gotten a mobile power station from a friend who was kind enough to leave it behind before graduating last year. In her words, “I don’t have any solar gadget; however, my friend who finished last year was nice enough to drop her power station for me and another friend for use.”

Samuel, Gerald’s classmate, also got a solar panel installed during the blackout. His decision was borne out of a tragic experience while trying to survive. According to him, “I had to get it after one of my devices got stolen while looking for where to charge.” After purchasing the solar-powered alternative, he shares similar sentiments with Gerald on its worth and how the UCH power is just an addition to what he already has.

In ‘developing’ countries like Nigeria, electricity is still regarded as a luxury, even in the 21st century and a national grid issue sends her citizens into an online disarray. On some occasions, Nigerians pour out their frustration in tweets stating how electricity has made them miss a life-changing opportunity. This is not so far-fetched even within the Alexander Brown Hall, UCH.

Speaking to John, the light schedule has made him miss deadlines. According to him, “I’ve had to reschedule a couple of meetings or even missed some because of the electricity issue. I’ve missed out on some other stuff related to work; I’ve also had to anticipate possible delays and, just in case I’m not able to charge, renegotiate or extend a deadline.” While relatively new Brownites like Ibukun and Michelle, a dental colleague, have not missed out on anything important due to light issues, older colleagues like Ore, in her final year in Dentistry, relate to that unpleasant occurrence.

As is characteristic of us to always find a way to survive and adapt, even if it means we are spending a few more dollars, Brownites have, over time, sought options that help them cope more.

Speaking to Osimenwu, she said “I got a big drum to store water for the days when we can’t pump due to no light. My power bank is solid and I also have this rechargeable table fan that helps when I can’t use my standing fan cuz of no light. Plus, I always make sure to charge my lamp so I can still do stuff even when there’s no light at night.” For John, the major expense so far has been a power bank, which is now faulty and needs a replacement. “Periods when I’ve had to go to UI to charge, I’ve had to spend more on transport. Also, for the most part, the financial implications aren’t as costly as the time itself,” he added. Glory, another Physiotherapy student, also had to get a rechargeable bulb, reservoir buckets for water, and is looking to get a power bank. Like many other Brownites, the morning schedule isn’t favourable as she would be out by 8:30am and not return earlier than 4:30pm.

While some Brownites find every means to keep their devices charged in school even if it means paying or going to UI, a few pack their bags and go home when it’s unbearable. Ore, in agreement, said, “I’m quick to pack my bags and go home when the going gets tough and it’s beyond what I can bear.” Glory, in like manner, also said “If it gets unbearable, I go home. I’m Ibadan-based.” For students that just moved into the hostel, it might become inevitable to deal with extra expenses just to live comfortably. Speaking with Michelle, she has plans to get a mini solar inverter to serve her needs. Michelle represents several residents who have weighed the pros and cons and deemed spending on solar alternatives a worthy cause in the long run.

Whether it’s the Brownite that has a solar panel, or the one with a heavy powerbank, or the one with four 25-litre kegs to store water, a common struggle they share is the insufficiency in electricity distribution to the place they call home for 4+ years. In a hostel filled with medical students, it’s not unusual to find people tucked in chairs in front of their reading tables late in the night. However, it takes extra tenacity and determination to consistently do that when power goes off at 11pm on the dot, EVERY NIGHT.

Patrick, a final-year dental student, describes the situation as heartbreaking. “It is heartbreaking as everywhere goes dark after 11pm, and I have to use different means (reading lamp, torch, phone, and power-bank enabled bulb) to illuminate my room/reading table because I usually do not sleep by 11,” he said. Patrick does not own a solar gadget, so his dependence is on a relatively new phone with an impressive battery life, supported by a power bank. While that feels relieving, the sustainability is bleak, to put it mildly. For Olamide, the power going off by 11pm only reminds many that Alexander Brown Hall has not been lit up through midnight in about 7 or 8 months. According to him, “A powerless midnight affects basically everything. There used to be heat (I think the weather is a bit cold now sha). Increased mosquitoes. Most importantly, it affects reading patterns very badly. It’s extremely more difficult using lamps to read in the room than when there’s power.”

It’s sickening that the foremost and self-acclaimed most prestigious teaching hospital in Nigeria runs on an eight-hour electricity supply per day, save for the rooms and wards with inverters and solar panels. What’s more despicable is the uncertainty and zero expectations of when all these rationing ends. On a non-existent paper, Brownites should get 8 hours of light per day; in reality, it could be less on the days when the clouds decide to grace the earth with a downpour. Rainy days even give the residents an obvious reason not to expect light. On some other days, blackouts and zero clue as to why that happened and everyone just keeps it moving, as long as they have decent clothes to wear to school and water to bathe/cook. It’s paradoxically a new normal that is abnormal and while adaptation seems to be the best option for an average Brownite, it only communicates to the powers that be that the bar can go lower and Brownites would dig deeper just so they attend school, satisfy examiners, and leave this vicinity not later than a day after swearing the Hippocratic oaths at the prestigious Paul Hendrickse Lecture Theatre, UCH, beautified in a fashion that hides the grotesque state of things.