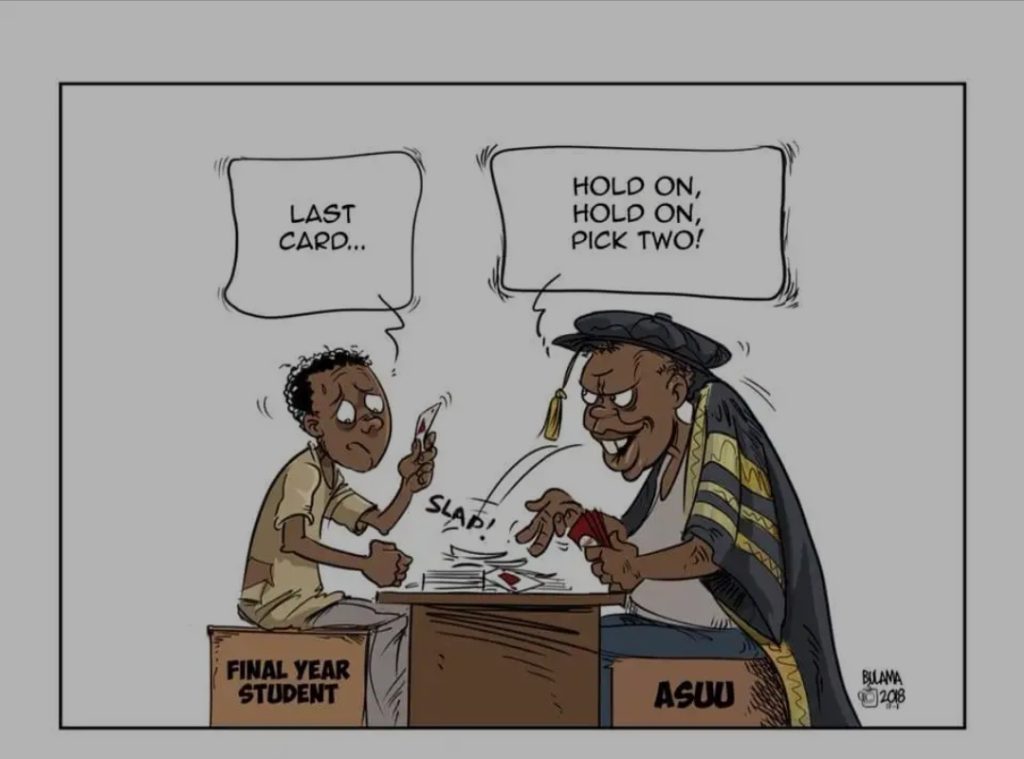

Just like in the game of cards where a turn of hands depicts everyone else’s fate, so was the ASUU strike. In this case, it was the fate of the Nigerian students. In the beginning, the strike was not “indefinite.” Here, ASUU was like a distraught judge mulling over a dilemma of whether to exercise its powers of the prerogative of mercy or not. For some students on most campuses, there was this confidence that the strike would not span more than four weeks. But the question begging for an answer is, “where did this confidence in the Nigerian government resolving the industrial dispute in record time emanate from?” Hence, some did not bother to leave their various campuses and few kept reading as if exams would sneak up on them like a thief in the night. Students who are solely responsible for themselves did not seek job opportunities.

On the 14th of March, “soon” turned into eight additional weeks. The number of students who had hoped that the strike would be called off reduced drastically. Again, on the 9th of May, the little semblance of optimism still found in a minute quantity of the Nigerian student populace fizzled out like the smell of a low quality, inexpensive perfume when the strike was rolled over for another 12 weeks. Nigerian students soon knew what they were in for and suspended academic work. Some went on to learn one or more skill and became certified while others ventured into business and service provision. The final lap before the strike was called off was the announcement of an indefinite strike on the 29th of August.

In the midst of all this, efforts were made to intervene in the fate-changing strike that had thousands of Nigerian students at home. During the first month of the ASUU strike, several measures (actions) were taken to ensure its suspension. The National Association of Nigerian Students (NANS) led by Mr. Sunday Ashefon, protested the strike in different states. These protests would then reoccur at intervals and each one would get Nigerian students one snail’s step closer to resumption.

It is noteworthy to mention that on the 9th of May when the strike was 12 weeks old, the ASUU NEC noted in a statement that the committee set up by President Muhammadu Buhari had yet to have a meeting with ASUU. In July, The Nigerian Labour Congress led a nationwide protest against the continued closure of Public institutions in Nigeria.The Intervention that started the process in ending the strike was spearheaded by The Speaker of The House of Representatives, Femi Gbajabiamila when he, on the 20th of September, called a stakeholders’ meeting to resolve the lingering crisis. He held a series of meetings with the ASUU representatives and with the pending court order issued to ASUU to return to work, the strike was called off.

This ordeal looked like one of those gory tales with a happy ending, but for this, it’s bittersweet. This series is incomplete without addressing the plights of people that were grossly affected by the ridiculous strike action. Students, entrepreneurs, on-campus vendors, and lecturers were all affected, to name a few. Many of these people surely have something to say about the eight-month-long strike. I’m very sure you would not want to miss the unfiltered opinions and feelings of the affected demography on your screens in subsequent volumes. Be expectant and stay tuned for volume three!

Peter Adeyemo and Afeezah Wojuade.