Born to Advantage: The NEPO vs. LAPO Reality

If you’ve been scrolling through X or tapping through WhatsApp statuses lately, chances are the NEPO vs LAPO baby memes have ambushed you, too. It’s the trend that crept in and suddenly was just everywhere—well, not that suddenly, more like a long-time squatter we just now noticed. So, what runs underneath the jokes that aren’t just jokes? Let’s dig in.

NEPO is short for nepotism, that magic key that opens doors not with skill, but with surnames. A NEPO baby is born not just with a silver spoon, but the whole cutlery set, sometimes engraved. These are the babies whose allowance could fund a small village, who get internships just by dropping a last name like it’s a cheat code.

LAPO, on the other hand, comes from the microfinance bank that helped many parents hold body when rice became gold. Remember those secondary school jokes about borrowing from LAPO and being locked in a dark room? Yep. A LAPO baby enters life with no spoon, maybe just a sachet of hope. They’re the kids who know how garri behaves in water, who’ve screamed “UP NEPA!” before every exam revision session. But what does this translate to in real life?

It’s a simple truth: where you start in life often determines how far you’ll go, even before you begin to try.

Take Aliko Dangote, for example. He started his business journey with a $3,000 loan from his uncle. Today, he’s the richest man in Africa. No one’s denying his business acumen, but let’s be honest: the average market woman in Bodija could probably achieve similar success if she had that kind of capital and a safety net.

So yes, being a NEPO baby means starting life on a foundation already built. The connections were made long before their first birthday. Trust funds were set up while they were still ultrasound images. They’re raised in an environment where dreams aren’t boxed up in a dark corner, watching as survival takes precedence. In their world, dreams are seeds only waiting to sprout.

And what about the LAPO baby? They get a barely-standard education. School fees are paid with loans from the parents’ cooperative or a salary advance. They grow up knowing that if they don’t hustle hard enough, they might not even be able to afford the same substandard education for their own children.

But here’s the catch—a NEPO baby may start 50 meters ahead in a 100-meter race, but that doesn’t guarantee he’ll get the gold medal. From where I see it, there are three kinds of NEPO babies:

- The Golden NEPO Baby: He grows up with everything, but he recognises it’s a privilege just a few are lucky to have, and he treats it as such. Even if he’s destined to inherit the family business with roots deeper than that of an iroko tree, he still works to sharpen his skills and make his own mark. His goal is simple—to capitalise on every advantage he has and turn it into something even greater.

- The Average NEPO Baby: He knows he’s got a safety net, and that knowledge makes him just…comfortable. He works, but only hard enough to keep things afloat. Maybe he’ll avoid crashing the family legacy, but he’s not necessarily equipped to take it to the next level. He lives somewhere between gratitude and entitlement.

- The Complacent NEPO Baby: He believes being born into wealth is the achievement. He acts like it. He’s the one who thinks anyone who doesn’t eat prawns airshipped from Japan is “struggling.” He doesn’t see a need to hustle or build anything new. After all, the trust fund is padded enough to last generations. Why stress?

Of course, there may be other NEPO kids somewhere in the middle of these types, but these are the average moulds we see, from my point of view.

For a LAPO baby, Life was already leading him 3-nil the moment he gave his first cry. He may start running five minutes after the race has begun, but that doesn’t make the gold medal impossible. From my point of view, there are three kinds of LAPO babies, too.

- The Golden LAPO Baby: He probably started from the very bottom rung of the ladder; hands bruised, palms bleeding from the climb. He learned early that his life was a choice between putting his hands in the dirt or eating it. Still, he dreamed and dared to allow his dreams to breathe. He believed that life could be better–it had to get better– and he worked like his life depended on it because it did. With discipline, tenacity, and a back-breaking dose of perseverance, he rises. And when he does, he doesn’t forget. He knows he has lived a lucky life, not because it was easy, but because he made it despite every reason not to. A great example is Seyi Adekunle, owner of Vodi, whose fashion empire now clothes some of Lagos’s biggest elites.

- The Average LAPO Baby: He’s caught in the in-between. He dreams too, but reality has a way of dimming his vision. He works hard, yes, but life throws too many curveballs. Maybe his schooling got disrupted. Maybe he had to become the breadwinner too early. Maybe there just wasn’t enough time to dream. He pushes through, does his best, and keeps afloat, but the fatigue shows. He’s neither fully defeated nor completely triumphant. He survives. And sometimes, survival alone is an achievement.

- The Not-So-Lucky LAPO Baby: You see this kind? They got the full LAPO package. Raised in a cramped house where ten people queue for the bathroom every morning, where their mother wakes up at 3 a.m. just to be first in the communal kitchen. They learned the meaning of hustle from the star— missing exams because of unpaid school fees, writing WAEC while working as a bus conductor to save for JAMB. They grew up knowing that if they didn’t take what they needed, no one would hand it to them. Years went by. Life didn’t hand them miracles, just more struggle. And so, they hustled in every way they could. Sometimes clean, sometimes in the grey. Some ended up in jail, serving time for a crime they committed from birth. Some ended up continuing the cycle, birthing children into the exact same conditions. They weren’t lazy or reckless. They were just products of the life they were born into, and the measures society put in place to ensure that they never got out.

However, these go beyond the personal stories. There’s a deeper, more complex relationship at play. It’s not just about who your parents are; it’s about the system that makes success hereditary. In a country where access to quality education is gated behind expensive private universities, where decent healthcare is a luxury for the cash-holding few, and where electricity, a basic utility, is stable only for those who can afford Band A, it’s no surprise that children raised in such contrasting climates grow up with vastly different starting lines.

And beyond these material inequalities, the system rewards proximity, not potential. A NEPO baby is born into a scaffold of soft landings—handshakes at age five turn into internships at sixteen and job offers before twenty-two. Meanwhile, an LAPO baby is stuck navigating a maze blindfolded, grinding for what the other was gifted at birth. For many LAPO babies, it’s not a lack of ambition; it’s the absence of a society that rewards effort with opportunity. They’re trapped in a structure where you either need to be undeniably exceptional or just the child of the right person. And let’s be honest: how many world-class prodigies can emerge from environments where survival is the first exam of the day?

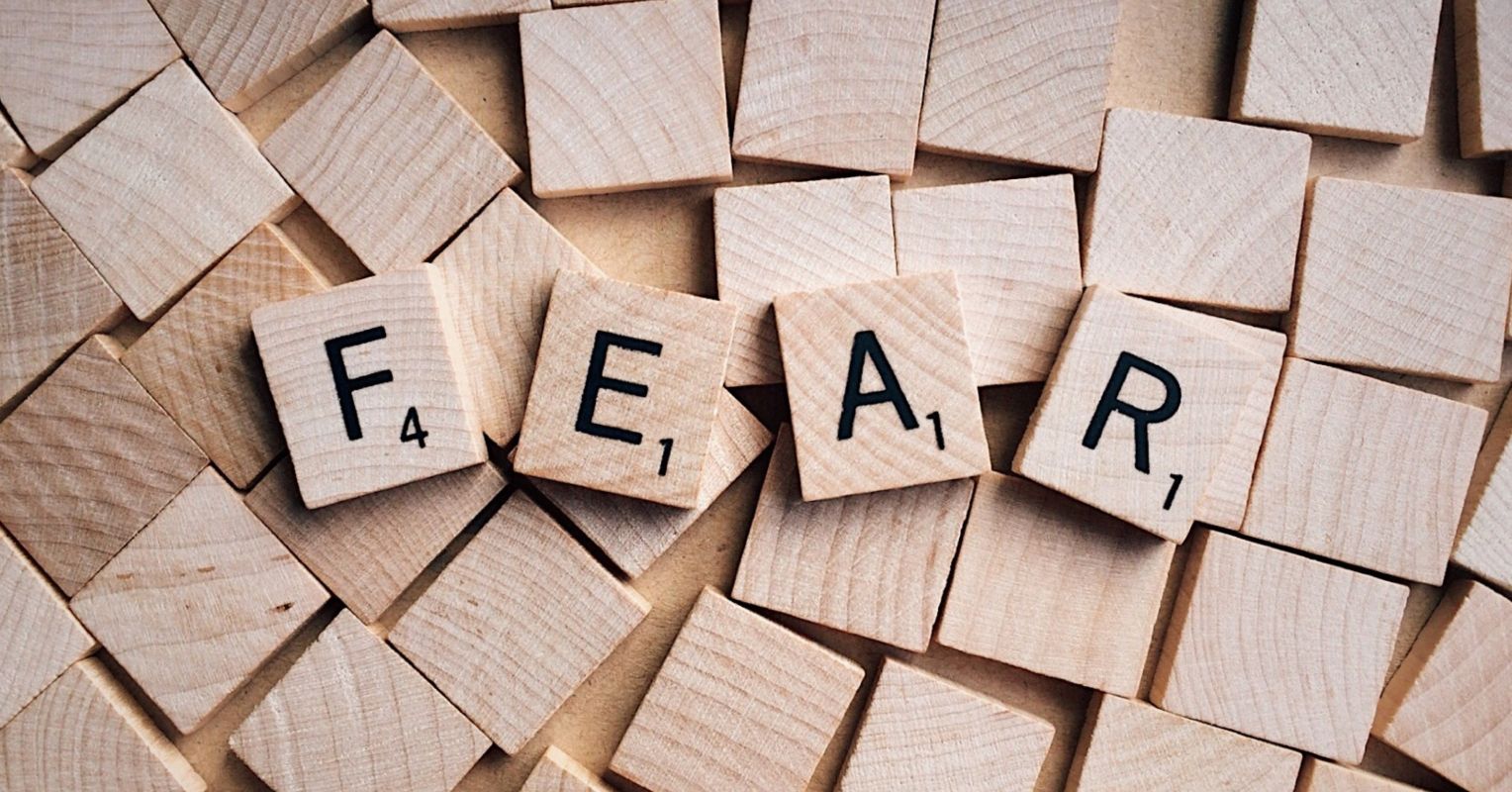

The cost isn’t just economic; it’s emotional, too. Many LAPO babies grow up in a constant state of performance anxiety, burdened by the silent fear that no matter how hard they work, the doors they need will remain locked. They’re told education is the key, but never that the locks have been changed. Depression, burnout and imposter syndrome aren’t foreign concepts; they’re everyday companions. Sometimes it’s not even sadness; it’s numbness. A quiet sense that maybe you’re running in circles, clapping for yourself, while the world only listens to last names and LinkedIn connections.

And even within the NEPO and LAPO categories, life isn’t fair in the same ways. A LAPO girl in the North faces double hurdles—poverty and patriarchy. A NEPO baby from a minority tribe may still get doors shut that others walk through without knocking. Even skin tone, accent, or the part of Nigeria you grew up in can tilt the game board.

The truth is: privilege isn’t just money. It’s location. It’s language. It’s a network. It’s perception. And let me be clear, I do not glorify pain. A LAPO baby doesn’t deserve more just because they had less, and hardship is no excuse for wrongdoing. Still, for every LAPO baby that stumbles or gives in, the system doesn’t get to wash its hands. It had a role to play.

At the same time, I don’t believe a NEPO baby’s success is invalid. It takes a different kind of discipline to know you could cruise on comfort, yet still choose the hard route, waking up early, pushing boundaries, striving for more. That takes grit, too. But let’s be honest: for many NEPO babies, success isn’t about escaping poverty or rewriting their future; it’s about proving a point, chasing dreams powered by passion, not pressure. They run towards something. LAPO babies often run from something—a life they desperately want to unlive.

So, there we have it.

A NEPO baby and a LAPO baby. Two individuals born into starkly different worlds. Childhood shaped them differently, and for many, it remains the greatest determinant of how far they go. But it’s not absolute. Where surnames open doors, talent can build new ones. Where family friends become internships, resilience kicks down walls. And while self-discovery brings fulfilment for some, for others, it’s the quiet joy of knowing they broke the cycle, that they made it out.

I see destiny as written in pencil and thus, subject to edits, rewrites, and bold new chapters. Your present is not your full story. Whether you’re an LAPO baby chasing the title of first graduate in your family, or a NEPO baby trying to carve a name beyond your father’s, you are valid. You are in charge. The world may hand you a script, but you still get to hold the pen.

Beautiful Article

This is top-notch

Nice piece 🪙